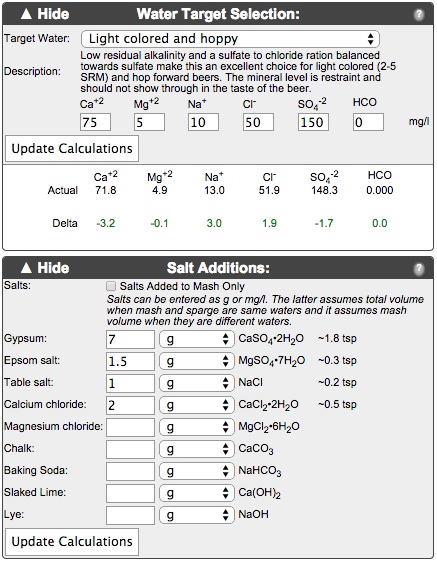

Matt Chrispen, a blogger at Accidentalis.com, shares some of his advice about water management for extract brewing. The first step: choosing the right water source.

Matt Chrispen, a blogger at Accidentalis.com, shares some of his advice about water management for extract brewing. The first step: choosing the right water source.

There is a myth that good tasting water makes good tasting beer… this is just not true. With many good water sources, you need to decide which will make the best beer. Water chemistry has less impact on the extract brewer, but starting with the right water will help you have the best chance at a great beer.

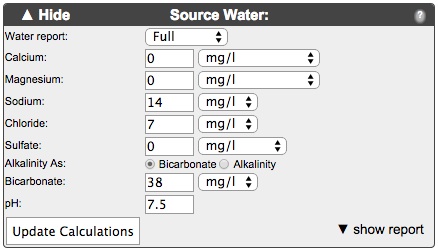

Tap Water: Tap water contains either chlorine or chloramines to deliver safe water to your home. These chemicals must be removed or will cause off-flavors to form in the beer that taste strongly of chemical plastics, vinyl, or iodine. Filtering slowly with active charcoal, letting the water stand, or boiling the water will remove chlorine, but treatment with potassium metabisulfite or Campden tablets will fully eliminate both chemicals. Often it is best to both filter and use Campden tablets. Tap water quality can also fluctuate due to seasonal issues.

- Using Campden Tablets: For brewing, use ¼ tablet per 5 gallons of brewing liquor. Crush the tablet and vigorously stir it into the bucket of water. The reaction is fairly immediate, and you may smell a bit of sulfur.

If you have a water softener, use the water tap before the softener to avoid excessive levels of sodium or potassium in the water.

Well Water: Professional tests should be run to ensure that organic, metallic, or chemical contamination is not present such as iron or fertilizer residue. If the water is safe, then evaluate its hardness. Low to moderately hard water, low in alkalinity is preferred for brewing.

Store Bought Spring Water: Most bottled spring waters are filtered (the treatment varies) and have re-mineralized the water ensuring a good taste. You can also purchase these in convenient 5-gallon carboys. The mineral concentration will be added to the minerals in the extract. However, the consistency of bottled spring water is preferable to seasonable quality changes that often affect tap water.

Tap, well and Spring Waters contain dissolved minerals that impart flavor and mouth feel to your beer. Be careful adding minerals, which might, in concert with minerals already in the extract, create strong mineral or metallic flavors. Experiment for the best results.

Tap, well and Spring Waters contain dissolved minerals that impart flavor and mouth feel to your beer. Be careful adding minerals, which might, in concert with minerals already in the extract, create strong mineral or metallic flavors. Experiment for the best results.

Reverse Osmosis (RO), De-Ionized (DI) and Distilled Water: Some stores offer filtered water products in bulk. In addition, home RO or RO/DI filters have become quite common and inexpensive. Distilled water is also a good choice. These water sources are really ideal for extract brewing, and offer the best basis for adding minerals as part of your beer recipe.

Water is the fundamental ingredient (up to 97%) in beer. Your tap water may make good beer, but try an alternative source and see if things improve. Choosing the best quality water will ensure your extract recipes have the best chance of becoming great beers!

In Part Two, we will explore the use of common mineral additions to enhance and tweak your extract and partial mash recipes.

———————————————————————-

Series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

———————————————————————-

Matt Chrispen is a passionate, experienced home brewer, craft beer fanatic, and collector of brewing gear. He also maintains a blog on advanced brewing topics at Accidentalis.com.

This is part 4 of cloning a Flower Power IPA from Ithaca Beer Co. In part one I discussed how I researched and went about

This is part 4 of cloning a Flower Power IPA from Ithaca Beer Co. In part one I discussed how I researched and went about

I recently shared my plans for making hard apple cider this year.

I recently shared my plans for making hard apple cider this year.

We would like to stop and take a moment to wish you the very best this holiday season. We sincerely hope that your Christmas is full of joy and excitement, and that the New Year brings you the brightest of days and provides you with all for which you strive.

We would like to stop and take a moment to wish you the very best this holiday season. We sincerely hope that your Christmas is full of joy and excitement, and that the New Year brings you the brightest of days and provides you with all for which you strive. After

After

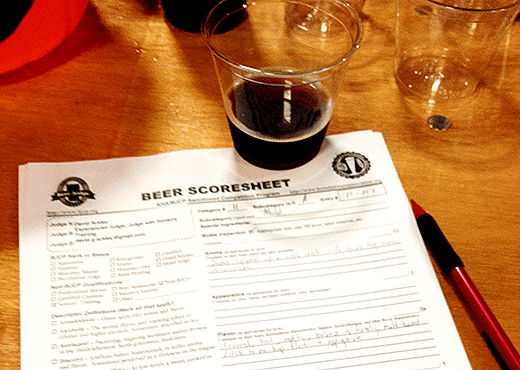

In the afternoon session of my recent BJCP beer judging experience, I was assigned to

In the afternoon session of my recent BJCP beer judging experience, I was assigned to

I recently had the opportunity to judge at a local homebrew competition.

I recently had the opportunity to judge at a local homebrew competition.