Some may get into homebrewing for the “do it yourself” challenge, some may start homebrewing to simply have fresh beer around the house, but others may take the step because they’ve fallen in love with a commercial beer and thought: “I could make this.”

Some may get into homebrewing for the “do it yourself” challenge, some may start homebrewing to simply have fresh beer around the house, but others may take the step because they’ve fallen in love with a commercial beer and thought: “I could make this.”

I know – I’m one of them.

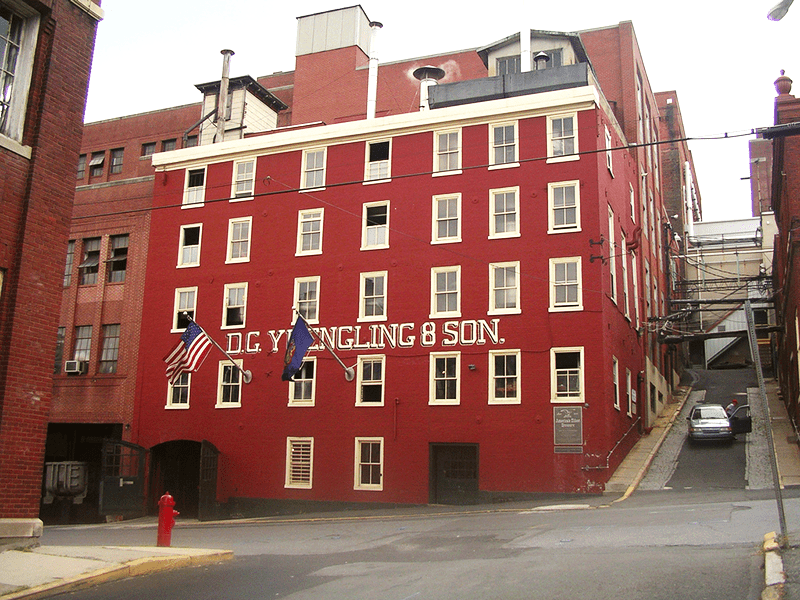

Peruse through this website or others and you’re bound to come across dozens – if not hundreds – of recipe kits at your disposal, from coffee stouts to hoppy IPAs and everything in between. But what may pique the interest of many is the ability to make “clone” beers using ingredient kits of such iconic brands as New Belgium’s Fat Tire or Samuel Smith’s Taddy Porter.

But why clone beer? It’s a good way to put your skills to the test. With that said, here’s my perspective on developing a clone beer recipe.

Developing a clone beer recipe to learn

Using prepared clone beer kits can be a good experiment in the homebrewing process, as you have a “control beer” to test your skills. Sometimes subtle differences in mash temperature, hop utilization, and grain bill can impact the final product. By making a beer and testing it side-by-side with the commercial version, you can get a better idea of what works best during your brew day and what you may need to pay more attention to.

I once made a Bass Pale Ale clone beer kit for the sheer challenge of trying to replicate one of the most famous versions of the style. While it ended up about 1 percent higher in alcohol content than I had hoped, it taught me to pay more attention to temperatures and how I was using my grains. It was a valuable lesson for future brew days.

If you want to clone beers yourself, the key to success is to hone your palate. As you build clone beer recipes, you’ll want to know what kind of ingredients to buy and how each piece impacts the larger puzzle.

One popular way both commercial brewers and homebrewers alike accomplish this is by brewing experimental beers, like single hop pale ales and IPAs as well as SMaSH beer recipes, which stands for “Single Malt and Single Hop.” In both cases, the goal is to hone the use of a specific ingredient so you can better understand it. Breweries like Mikkeller, Flying Dog, and even Sam Adams have produced single-hop beers as a means for consumers to taste the subtle differences between two different hop varieties, like Citra and Sorachi Ace, for example.

Develop a clone beer recipe to replicate your favorites

One of the first cloned beer recipes I made was a watermelon wheat beer based off of 21st Amendment’s famous Hell or High Watermelon Wheat. Sipping the California brewery’s fruit-laced beer from the can, I thought I might like to try this beer, but with more intense watermelon taste.

To make my own personal take on the clone beer, I looked up a clone recipe. Instead of using natural flavoring, I wanted to go for the real thing, so I sanitized two watermelons, cut them up and squeezed juice from them to add to my secondary. The result: a beer that tasted quite like a boozy watermelon. Unique, for sure.

One of the best parts of homebrewing beer is the ability to experiment, and cloning gives you the perfect opportunity to do just that. We all have different palates, and the aromas and tastes we experience may be better served with a tweak or two of our favorite commercial beers.

No matter why you choose to develop a clone beer recipe, it’s one more tool in your toolbox (or is it bottle in your six-pack?) to help you become a better homebrewer. If you’re ready to take the plunge, check out “North American Clone Brews,” which offers 150 clone beer recipes for brewing beers from Anchor, Sierra Nevada, Fat Tire, Samuel Adams and more. Each of the clone beer recipes come with an extract, partial mash and all-grain version for homebrewers of any skill set.

—–

Bryan Roth is a beer nerd and homebrewer living in Durham, North Carolina. You can read his thoughts on beer and the beer industry on his blog, This Is Why I’m Drunk, and send him suggestions on how to get his wife to drink craft beer via Twitter at @bryandroth.