Every homebrewer gets the urge at some point to add a little something special to their beer. I’m guessing it has to do with the fact that you can easily find a stout at the store, but a mint chocolate stout? Now that’s something special!

Every homebrewer gets the urge at some point to add a little something special to their beer. I’m guessing it has to do with the fact that you can easily find a stout at the store, but a mint chocolate stout? Now that’s something special!

One popular way of adding flavors to homebrew is what Randy Mosher calls a potion. This is essentially a mixture of alcohol and whatever flavoring ingredient you want in your beer. Another term for this is an extract. That’s what this post is about, how to make and use these potions or extract to flavor your homebrews.

So what kinds of potions can you make?

Though you can make a potion out of just about anything, here are a few of the most common:

- vanilla

- cacao/chocolate

- orange peel

- mint

- cardamom

- coffee

- licorice

The main benefit of using a potion or extract is that it’s easy to adjust how much of the flavor you want in the beer. It can be difficult, for example, to figure out how much flavor three vanilla beans might bring to your vanilla porter. With an extract of vanilla bean, all you have to do is take a sample of beer and use a dropper to measure how much of the potion is needed to reach the intensity of flavor you want. Then you scale up to figure out how much to add to your batch.

The main drawback of using a potion is that it takes some foresight. To fully extract the flavor from your ingredient of choice, you will need to let it soak in alcohol for at least a week, ideally three or four. This means that if you plan to add your potion at bottling time, it should be prepared on brew day or even several days before. Just be sure to use a digital scale to measure how much of the ingredient you added to the jar. Save this information in your brewing notes so you can recreate the potion if you want to.

How to Add a Potion to Your Homebrew

How to Add a Potion to Your Homebrew

- Choose a flavoring ingredient that will blend well with your beer style.

- Buy some cheap vodka or similar alcohol.

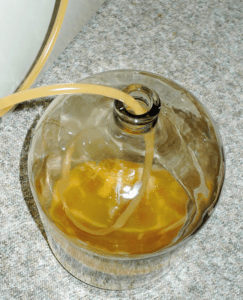

- Put the ingredient in a mason jar and pour in enough liquor to fully cover the ingredient.

- Let sit for about three weeks.

- When it’s time to add the potion to your beer (usually bottling day), take a measured sample of beer for a taste test.

- Use a measured dropper or pipette (ideally in fractions of a milliliter) to add small amounts of potion to the beer until desired flavor is reached.

- Scale up to figure out how much potion to add to your homebrew.

Example:

Let’s say you find that 1 mL of potion is ideal for eight ounces of beer. There are 80, eight-ounce servings in five gallons of beer, so add 80 mL of potion to your homebrew.

Sounds easy enough, right?

Making flavor extracts for your homebrew is just one more way to add a lot of fun to the process. It’s one more avenue for a lot of creativity. What kind of beer would you make with your homemade potion?

—————————————————————–

David Ackley is a beer writer, homebrewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

One of the hardest parts of homebrewing is the waiting – especially after the beer has been bottled or kegged. But this is an important time for the beer. You could call it a “self discovery” phase. Brewers call it conditioning.

One of the hardest parts of homebrewing is the waiting – especially after the beer has been bottled or kegged. But this is an important time for the beer. You could call it a “self discovery” phase. Brewers call it conditioning.

Can you tell me when to add water to my wine, is it during fermentation or after? I make wine using Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel grapes mixing 50 /50, but it always comes out very strong, I like that smooth taste, any suggestion?

Can you tell me when to add water to my wine, is it during fermentation or after? I make wine using Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel grapes mixing 50 /50, but it always comes out very strong, I like that smooth taste, any suggestion?

Adventures in Homebrewing is proud to announce an expanded offering of

Adventures in Homebrewing is proud to announce an expanded offering of  After being out of town for the holidays, I returned home, opened my fermentation chamber, and inspected the

After being out of town for the holidays, I returned home, opened my fermentation chamber, and inspected the