Why not try something a little different? How about brewing an Irish red ale beer recipe? It’s a great option for those who prefer some malty sweetness over a dry, roasty flavor in their homebrews.

Why not try something a little different? How about brewing an Irish red ale beer recipe? It’s a great option for those who prefer some malty sweetness over a dry, roasty flavor in their homebrews.

Almost every American beer drinker knows of Killian’s Irish Red, but some might dispute the authenticity of that beer, now made by Coors. Dig a little deeper at your favorite beer store to find other examples of Irish red ales. Believe or not, they make more than just stouts in Ireland! See if you can get your hands on a Smithwick’s or Murhpy’s Irish Red for a true Irish red ale. Countless microbreweries also have their own version of an Irish red ale.

The Irish red ale beer recipe below yields a sessionable brew at just 4.8% ABV and about 17 IBUs. Looking for something your Irish drinking buddies would really be proud of? Feel free to increase the malt extract or base malt by as much as 50% for a higher gravity beer, and/or increase the hop additions to manipulate bitterness, flavor, and aroma as you see fit.

Happy brewing!

Irish Red Ale Beer Recipe (via Homebrewing for Dummies)

(5-gallon batch, extract with specialty grains)

Specs

OG: 1.049

FG: 1.012

ABV: 4.8%

IBUs: 17-18

SRM: 15

Ingredients

6.6 lbs. golden light malt extract syrup

1 lb. crystal 60L malt

2 oz. black malt

0.5 oz. Fuggles hops at :60

0.5 oz. Fuggles hops at :40

0.5 oz. Fuggles hops at :20

0.5 oz. Kent Goldings hops at :5

1 pack Wyeast 1084: Irish Ale Yeast

Directions

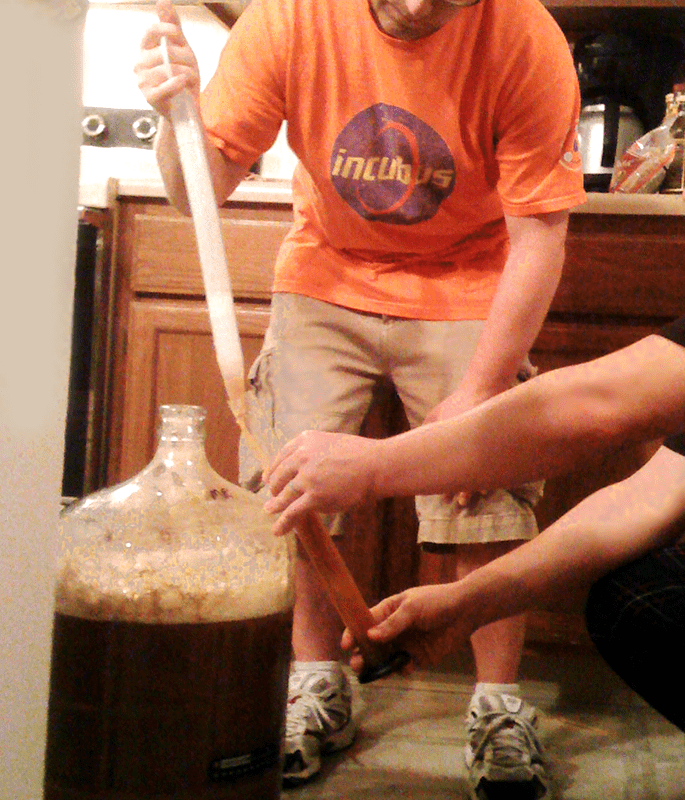

The day before brewing, prepare a 2L yeast starter. On brew day, heat three gallons of clean, chlorine-free water to about 150˚F. Place the specialty grains in a muslin grain bag and steep for 20-30 minutes. Remove specialty grains and mix in liquid malt extract. Bring wort to a boil and boil for 60 minutes. Add hops according to schedule above. At end of boil, cool wort to 65˚F and transfer to a clean, sanitized fermenter. Mix in enough clean, chlorine-free water to make five gallons and pitch yeast starter. Ferment at 65˚F until complete.

All-Grain Directions

Replace the LME with 8.8 lbs. Maris Otter malt. Combine with the specialty grains and mash for 60 minutes at 150˚F. Lauter and sparge to collect about 6.5 gallons of wort in the brew kettle. Proceed with recipe above, but reduce the 60-minute hop addition to .25 oz.

about 6.5 gallons of wort in the brew kettle. Proceed with recipe above, but reduce the 60-minute hop addition to .25 oz.

Brewing the Irish red ale beer recipe above is a lot of fun, but if you’re looking for a recipe kit, instead? Try the Steam Freak Dublin Docks Red Ale! It’s a partial mash kit that comes with all the ingredients (pre-measured) and specific instructions to take you through the process.

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, homebrewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

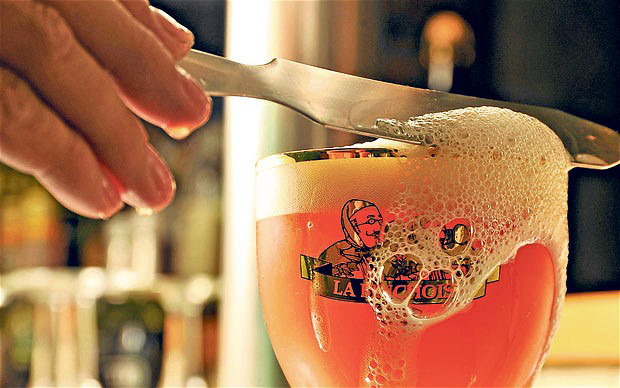

Belgian beers have become all the rage in the United States. Some might even credit them as inspiring the American craft beer movement. Belgian-style beers are characterized by the use of Belgian beer yeast, which produces a wide range of fruity and spicy notes that often make Belgian beers wine-like in their complexity. If you’re a fan of Belgian beers, here are the 7 best Belgian beer recipes that you should try right away:

Belgian beers have become all the rage in the United States. Some might even credit them as inspiring the American craft beer movement. Belgian-style beers are characterized by the use of Belgian beer yeast, which produces a wide range of fruity and spicy notes that often make Belgian beers wine-like in their complexity. If you’re a fan of Belgian beers, here are the 7 best Belgian beer recipes that you should try right away: