In home winemaking for the keep-it-simple winemakers, you toss yeast into wine must and see what happens. What’s the problem here? There are a lot of problems here, but the one we are referring to relates to the ability of that yeast to complete a wine fermentation. One major component that’s missing from this equation is yeast nutrients! Just as humans need sustenance to move and be active, wine yeasts also need nutrients to keep their metabolism going and to keep the fermentation going strong. But what are yeast nutrients in wine making?…

In home winemaking for the keep-it-simple winemakers, you toss yeast into wine must and see what happens. What’s the problem here? There are a lot of problems here, but the one we are referring to relates to the ability of that yeast to complete a wine fermentation. One major component that’s missing from this equation is yeast nutrients! Just as humans need sustenance to move and be active, wine yeasts also need nutrients to keep their metabolism going and to keep the fermentation going strong. But what are yeast nutrients in wine making?…

For wine yeasts, it takes a heck of a lot of energy to multiply themselves into a viable colony, then turn the sugars of the juice into alcohol and carbon dioxide, so their energy really needs to be thoroughly replenished in order for them to not give up and die from exhaustion. The alternative is a stuck fermentation where the yeast activity comes to a complete halt. Wine yeasts are living creatures (yes, they are teeny tiny, but they are still alive and kicking!), and they need to have their nutrients replaced when it is depleted through the rigorous activity of fermentation!

OK, so your wine yeasts need yeast nutrients in order to avoid a stuck or stopped fermentation. What do I give them? Multivitamins? Pasta primavera? Red Bull? Surely those items will cause more harm than good for your wine, so instead, we’ll recommend some nutrient products for your wine yeast to munch on in order to ensure your wine fermentation keeps on going until the end.

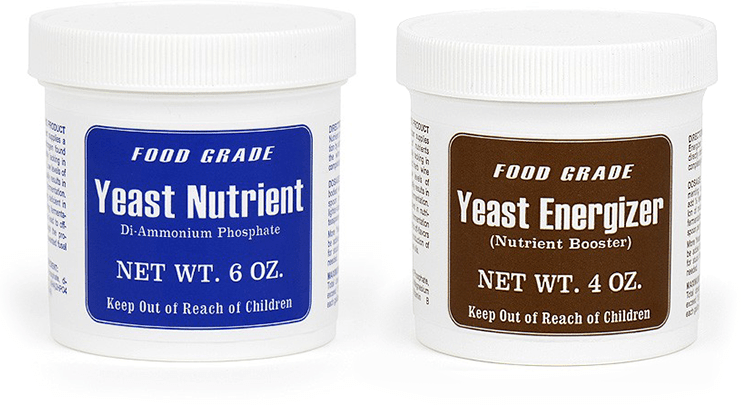

- Di-Ammonium phosphate: This is a common ingredient in a lot of wine yeast nutrients, and is the primary ingredient in the product Yeast Nutrients. Basically, the yeasts utilizes the nitrogen component of the Di-Ammonium phosphate in order to supply the energy they need to keep that fermentation going strong. Nitrogen to the wine yeast is like oxygen to us humans. How much Yeast Nutrient to add will depend upon what kind of wine you are making, You can always add more Yeast Nutrient later if your fermentation becomes sluggish, so don’t worry too much if you think you aren’t adding enough.

- Yeast Energizer: Sometimes when the yeast nutrients you added aren’t enough, you end up with a slowing, sluggish, or otherwise stuck fermentation. Yeast Energizer is a great product to help jump-start the fermentation again and get your wine back on track. The primary ingredients in Yeast Energizer are Di-Ammonium phosphate (the same stuff we’ve seen before), yeast hulls, magnesium sulfate, vitamin B complex, and tricalcium phosphate. Not only will these ingredients help re-start your fermentation, but they also will ensure that your wine fermentation will keep going and at a rapid rate.

As a general rule-of-thumb, Di-Ammonium phosphate is used by itself with wines made from grapes or hearty fruits similar to grapes such as bush-type berries. But as you start making wines with fruits that are more dissimilar to grapes, you are more likely to need Yeast Energizer. Herb wines such as dandelion, rose hip are prime candidates for Yeast Energizer, as is honey wine or mead. If you are following a wine recipe it will most likely tell you which type of yeast nutrient to use in your wine.

Remember, a wine that is lacking in yeast nutrients will not only cause a slow, sluggish, or even stuck fermentation, but can cause off-flavors and aromas in your finished wine. So, don’t forget to feed your yeasts!

—–

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

Sometimes it’s fun to brew outside of the BJCP style guidelines and to combine different beer styles to make something new and different – a hybrid beer style if you will. Today’s all-grain, rye porter beer recipe combines the roasted malt flavors of a porter with the spicy, tangy rye flavors of a rye pale ale.

Sometimes it’s fun to brew outside of the BJCP style guidelines and to combine different beer styles to make something new and different – a hybrid beer style if you will. Today’s all-grain, rye porter beer recipe combines the roasted malt flavors of a porter with the spicy, tangy rye flavors of a rye pale ale.