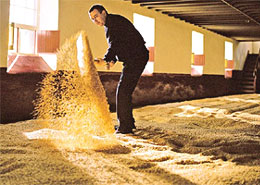

Many homebrewers have looked at the pile of spent grains after their mash and wondered, “Isn’t there something I can do with all these spent grains?”

Many homebrewers have looked at the pile of spent grains after their mash and wondered, “Isn’t there something I can do with all these spent grains?”

Well in fact, there is! In addition to composting your spent grains or making spent grain dog treats, you can reserve those grains and incorporate them into just about any bread recipe. Here’s how to make spent grain bread:

- First of all, don’t use the spent grains if you’ve added any hops to the mash. This can result in unpleasantly bitter beer bread.

- Unless you intend to use the grains right away, put them in the freezer. Warm, wet grains can get stinky pretty quick! You’ll only need about 2-4 cups of spent grains for a loaf of bread. Discard the rest, compost them, or freeze them until you want to cook with them.

- Your bread will have a smoother texture if you can process the spent grains in a food processor. If you don’t have a food processor that’s ok – just proceed with the recipe.

- Follow the recipe below on how to make spent grain bread!

Recipe: Spent Grain Bread

(makes 1-2 loafs)

Ingredients

- 1 cup warm water (you can also use a flat, malt-forward beer, such as porter or brown ale at room temperature)

- 2 tbsp sugar, honey, or maple syrup

- 2 tbsp vegetable oil or olive oil

- 2 tsp active dry yeast (you can also use beer yeast!)

- 2 tsp salt

- 4 cups all purpose flour

- 2 cups spent grain

Directions

- Mix together the liquid ingredients (water/beer & oil) in a mixing bowl. Mix in the sugar and yeast and set aside for 5-10 minutes.

- Place the spent grains in a large mixing bowl. Mix in the all purpose flour and salt and mix well. Don’t be afraid to get messy!

- Form a well in the middle of the dough and pour in the liquid ingredients. Mix well.

- Form the dough into a ball. The dough should be easily pliable, but not sticky. If your dough is sticky, knead in more flour.

- Oil a mixing bowl and place the dough in the bowl to rise. Give it 60-90 minutes.

- At this point, the dough should have risen. If it didn’t, you may need more yeast, or a fresh batch of yeast.

- Punch down the dough, roll it into a nice loaf and place it in a greased bread pan or on a greased baking sheet. Let the dough rise for another 60-90 minutes.

- Heat your oven to 350˚F.

- Bake the bread for about one hour. The bread is done when a toothpick stuck into the middle of the loaf comes out clean.

- Smother your bread with butter, make a sandwich, or make French toast – enjoy!

And there you have it, how to make spent grain bread. What do you do with your spent grains? We’d love to hear your ideas!

——————————————————————————————————-

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder and editor of the Local Beer Blog.

When I used my 6 gallon primary fermenter previous, I notice that the “full” line is actually a bit lower than the top of the fermenter. I’m not certain if it was 1.5L of space, but I would like to think that it was. From the line drawn on the 6 gallon point on the outside of the fermenter, it looks like there is plenty of space for 1.5 more liters of “stuff”. I’ll have to ask the friendly folks as ECKraus about this, but I wanted to express my concerns to you all first, in case one of you has had experience with this and might be able to give me some advice.

When I used my 6 gallon primary fermenter previous, I notice that the “full” line is actually a bit lower than the top of the fermenter. I’m not certain if it was 1.5L of space, but I would like to think that it was. From the line drawn on the 6 gallon point on the outside of the fermenter, it looks like there is plenty of space for 1.5 more liters of “stuff”. I’ll have to ask the friendly folks as ECKraus about this, but I wanted to express my concerns to you all first, in case one of you has had experience with this and might be able to give me some advice. My name is Leigh Erwin, and I am a brand-spankin’ new home winemaker! E. C. Kraus has asked me to share with you my journey from a first-time dabbler to an accomplished home winemaker. From time to time I’ll be checking in with this blog and reporting my experience with you: the good, bad — and the ugly.

My name is Leigh Erwin, and I am a brand-spankin’ new home winemaker! E. C. Kraus has asked me to share with you my journey from a first-time dabbler to an accomplished home winemaker. From time to time I’ll be checking in with this blog and reporting my experience with you: the good, bad — and the ugly. I’m new and I think I just ruined my first 3 gallons of peach wine. I had everything ready to go to bottle and I went back to the internet to check the amount of potassium metabisulfite to add. I was sure I read 1 teaspoon per gallon prior to bottling, but noticed a really strong SO2 odor when I dumped the small amount of wine left in the 3 gallon carboy while cleaning up. I went back to check the amount again and found anywhere from 1/16th to 1/4 of a teaspoon is what I should have used. I had already corked the bottles at this point and now I don’t know if it can be salvaged. Will it break down if I leave it to age longer?

I’m new and I think I just ruined my first 3 gallons of peach wine. I had everything ready to go to bottle and I went back to the internet to check the amount of potassium metabisulfite to add. I was sure I read 1 teaspoon per gallon prior to bottling, but noticed a really strong SO2 odor when I dumped the small amount of wine left in the 3 gallon carboy while cleaning up. I went back to check the amount again and found anywhere from 1/16th to 1/4 of a teaspoon is what I should have used. I had already corked the bottles at this point and now I don’t know if it can be salvaged. Will it break down if I leave it to age longer? I am still new to winemaking, starting my second batch, my question is: I started my yeast in a separate bottle, started to ferment just fine, added it to my wine base, is not doing anything. I have warmed up my base, has now been @ 48 hours. Do I need to add more yeast? Am I loosing my base, now spoiled? Not sure what else to do to get yeast going.

I am still new to winemaking, starting my second batch, my question is: I started my yeast in a separate bottle, started to ferment just fine, added it to my wine base, is not doing anything. I have warmed up my base, has now been @ 48 hours. Do I need to add more yeast? Am I loosing my base, now spoiled? Not sure what else to do to get yeast going.

I made my first 5 gallons of plum wine last fall and it turned out really well. Recently I decided to try making grape wine using frozen grape concentrate. I figured on only doing a gallon to start with before making a larger batch. I used a plastic gallon milk jug for the primary fermentation and after the second day decided to stir the wine. That turned out to be a huge mistake! As soon as I started to stir, there was a violent reaction and grape juice shot about 5 feet up the wall and made a big mess. Before it settled down I lost about a quart of the product and now I am not sure what to do. Can I just go ahead and top it off with water or do I need to start over? Also, what caused the violent reaction in the first place? Thanks for any advice you can provide.

I made my first 5 gallons of plum wine last fall and it turned out really well. Recently I decided to try making grape wine using frozen grape concentrate. I figured on only doing a gallon to start with before making a larger batch. I used a plastic gallon milk jug for the primary fermentation and after the second day decided to stir the wine. That turned out to be a huge mistake! As soon as I started to stir, there was a violent reaction and grape juice shot about 5 feet up the wall and made a big mess. Before it settled down I lost about a quart of the product and now I am not sure what to do. Can I just go ahead and top it off with water or do I need to start over? Also, what caused the violent reaction in the first place? Thanks for any advice you can provide. At one time, both Ireland and Scotland were part of the British Empire. (Today, the Republic of Ireland is a sovereign nation.) There is evidence of brewing in Scotland and Ireland dating back hundreds, if not thousands of years. More recently, both countries have contributed a variety of distinct beer styles to the world of brewing, a few of which are listed below.

At one time, both Ireland and Scotland were part of the British Empire. (Today, the Republic of Ireland is a sovereign nation.) There is evidence of brewing in Scotland and Ireland dating back hundreds, if not thousands of years. More recently, both countries have contributed a variety of distinct beer styles to the world of brewing, a few of which are listed below. I purchased a winemaking kit that came with fresh juice from a local winery. The process was not explained well in the class, and it turns out I added water to the fresh juice in error (instructions did not differentiate between fresh and concentrated juice). The juice does contain 50% water, and has been in the refrigerator since (about 2 months). Is this juice still usable to make a batch of wine? If so, is it worth it since it is watered down? I don’t even know if adding water to the fresh juice is okay to produce an okay wine? Thanks for any and all help!

I purchased a winemaking kit that came with fresh juice from a local winery. The process was not explained well in the class, and it turns out I added water to the fresh juice in error (instructions did not differentiate between fresh and concentrated juice). The juice does contain 50% water, and has been in the refrigerator since (about 2 months). Is this juice still usable to make a batch of wine? If so, is it worth it since it is watered down? I don’t even know if adding water to the fresh juice is okay to produce an okay wine? Thanks for any and all help! Hey everybody! Leigh here! Just checking in with you all to update you on how everything is going in “new home winemaker land” over here!

Hey everybody! Leigh here! Just checking in with you all to update you on how everything is going in “new home winemaker land” over here!