Guest blogger Billy Broas delivers sound advice for selecting the right yeast strain for your homebrew:

Guest blogger Billy Broas delivers sound advice for selecting the right yeast strain for your homebrew:

—–

Beer yeast is an underappreciated ingredient in homebrewing. Sure, we know that we must take the right steps to keep it happy: make a yeast starter, control the temperature, aerate, etc. But yeast’s flavor impact on the final product is often overlooked. Sometimes we forget that selecting beer yeast that is appropriate is just as important as nurturing the beer yeast we select.

If you’re trying to brew a beer strictly to style, then it’s best to choose a traditional beer yeast strain. In general, go with an American yeast strain for American styles, an English strain for English styles, etc.

Sometimes when selecting beer yeast you choose a traditional strain, but aren’t happy with the results. You might be tempted to switch to a different beer yeast, but don’t forget about all of the different variables that affect yeast character. The beer yeast you select may actually be perfect, but you pitched it a little too warm.

Pitching temperatures, fermentation temperatures, time, and even fermenter shape all impact the flavor you get from a beer yeast when homebrewing. Try tweaking these variables before jumping strain to strain. I was never a big fan of Wyeast 3068 (the Weihenstephan strain), but once I figured out the correct fermentation temperature it became my favorite strain for German ales.

Of course you don’t always need to go by beer style guidelines. Much of the fun in homebrewing is experimenting. You could try a German Ale yeast in an American Pale Ale or a Bohemian Lager yeast in an Irish Stout. If you factor in the variables mentioned above like temperature and aeration, the potential new flavor profiles become endless.

In addition to flavor and aroma, the beer yeast you select will have a big impact on the mouthfeel of the beer. Have you ever made a beer that tasted too thin? Maybe it finished at a very low gravity and dried out too much. A common corrective action is to use more grain to make a “bigger” beer. Or maybe you add some CaraPils to provide more dextrins.

Perhaps the best solution though is selecting beer yeast with lower attenuation – one that doesn’t ferment that last bit of carbohydrates out of the beer. You can keep the rest of the beer recipe the same and because the new strain won’t ferment as many sugars, the final gravity will be higher, resulting in a fuller-tasting beer.

For example, I love using WLP007 Dry English Ale yeast for my English Pale Ales and IPAs, but my English Mild is too low in gravity for that yeast. It’s a 1.035 original gravity beer, so the WLP007 would make it very thin tasting. To give it more body I use a less attenuation English Ale yeast, such as WLP002.

Selecting beer yeast is not a thoughtless task. Choose your beer yeast wisely when homebrewing, and most importantly, take notes on your batches. With time you’ll find the best beer yeast strain for all of your favorite beer recipes!

—–

Billy Broas is a BJCP beer judge and the homebrewing expert on the Rocky Mountain PBS television show “Colorado Brews.” He teaches an online homebrewing class at The Homebrew Academy and runs a blog about craft beer at BillyBrew.com.

Category Archives: Beer Brewing Ingredients

How To Brew Witbier

Witbier, or bière blanche, in French, is a style of wheat beer native to Belgium. Belgian “white” beer is characterized by its light color and cloudy appearance, usually from the use of unmalted wheat or oats. Moderately hopped, Belgians wits are commonly flavored with coriander, bitter orange peel, and possibly other spices as well. Given its light, fragrant, and refreshing qualities, belgian witbiers are perfect for brewing and drinking in warmer weather. (Can you tell I’m excited for summer?!) So, here’s some insights on how to brew Witbier.

Witbier, or bière blanche, in French, is a style of wheat beer native to Belgium. Belgian “white” beer is characterized by its light color and cloudy appearance, usually from the use of unmalted wheat or oats. Moderately hopped, Belgians wits are commonly flavored with coriander, bitter orange peel, and possibly other spices as well. Given its light, fragrant, and refreshing qualities, belgian witbiers are perfect for brewing and drinking in warmer weather. (Can you tell I’m excited for summer?!) So, here’s some insights on how to brew Witbier.

Though once popular throughout Belgium, wits were nearly made extinct until Pierre Celis revived the style in the 1960s. Today, almost every beer drinker knows of Hoegaarden, named for the town where witbiers were made popular, and Blue Moon, the interpretation of the style made by Coors.

In doing some research for this post, I found an interesting tidbit from Michael Jackson, which explains how the Curaçao orange peel and other spices may have found their way into witbiers. In his Beer Companion, he points out that “Belgium was a part of the Netherlands when many spice islands, including the orange-growing territory of Curaçao, were colonized.” It stands to reason that the spice trade influenced what was used in the brewing of witbiers.

Modern interpretations of the style may include some interesting flavoring ingredients. Westbrook Brewing in South Carolina makes a wit called White Thai, which uses lemongrass and ginger root instead of orange peel and coriander.

How To Brew Witbier

Witbiers are a fun style to brew and one that you and your non-beer geek friends will likely enjoy throughout the summer. Our Brewcraft Belgian Wit recipe kit includes everything you need to brew a Belgian white. You can also brew your own Blue Moon with Stream Freaks Blue Noon recipe kit. Both of these recipe kits are from extract. If you prefer to formulate your own witbier recipe, read on.

- Grains – Extract brewers will want to use the lightest malt extract available, probably using a fair amount of wheat malt extract syrup, an extract made from both wheat and barley malt (65/35 wheat to barley malt). All-grain brewers should start with a light pilsner malt for the base of their grain bill. Both might consider using unmalted wheat or oats for added body and the notorious witbier cloudiness.

- Hops – Traditional European varieties of hops should be used in an authentic Belgian witbier, but feel free to use some American hops if you’d like. According to Michael Jackson, the original Hoegaarden used East Kent Goldings and Saaz, though I’m not sure that’s still the case now that Hoegaarden is owned by AB-InBev. In any event, shoot for 10-20 IBUs.

- Herbs & spices – Coriander and bitter orange peel are the common additions in Belgian whites. Hoegaarden’s “secret” spice is believed to be grains of paradise. This is a good style though for thinking outside the box, so you may wish to throw in some lemon peel, lemongrass, ginger, or chamomile into your witbier depending on your tastes.

- Yeast – Use a wit beer yeast or other Belgian yeast strain for your witbier.

That’s my take on how to brew Witbier. Are you a fan of Belgian wits? How do you like to brew your own Belgian white?

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

Storing Hops: What's The Best Way?

The question often comes up: “I’ve had this bag of hops in the refrigerator for over a year…can I still use them?”

The question often comes up: “I’ve had this bag of hops in the refrigerator for over a year…can I still use them?”

In short, yes! However, just storing hops in the refrigerator does not preserve their alpha acids very well, which makes it difficult to predict how they will affect a beer’s bitterness. Hops lose their potency and freshness over time, and only in the case of Lambics are aged hops considered desirable. Further, if not stored properly, hops can absorb some unpleasant odors wafting around your fridge, so it’s important to understand the proper method of storing hops in order to brew the freshest, best beer possible.

So, what’s the best way to store hops?

Learning how to store hops is a piece of cake:

- Good – At a minimum, keep your hops in the refrigerator in an airtight container—like in a mason jar—and use them as soon as possible after purchasing.

- Better – Even better, store hops in a vacuum-sealed package in the refrigerator. A consumer grade vacuum sealer can come in handy for this purpose.

- Best – The best method for storing hops is to keep them in an air-flushed, vacuum-sealed package in the freezer. Most homebrewing hops these days are packaged and stored this way. If it will be more than a few days before brewing with the hops, just toss them in the freezer until brew day.

The same goes for storing hops after opening the package. If you have an unused portion of hops, storing the hops in the freezer in an airtight container is the best way to go. Try to use the hops as soon as possible.

What if my hops are old? Can I still use them? How does this affect IBUs?

If your have been storing hops in the freezer in an airtight container for less than a year, you should be able to use them without their age having a negative affect on your beer.

If the hops have been stored for longer than a year or just kept in a refrigerator, it might be a good idea to calculate the actual alpha acid content of the hops in order to accurately predict IBUs in the finished beer. All hops should be packaged with an alpha acid content expressed as a percentage. From there, it’s a simple matter of using an aged hop calculator to adjust the alpha acid content and the weight needed to achieve a desired bitterness level.

Keep in mind that there are many factors affecting bitterness in beer, so calculated IBUs are just an approximation. At the end of the day, it may be worth just buying some fresh hops from the homebrew shop so you can be sure you get the best qualities from your hops as possible.

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder and editor of the Local Beer Blog.

Harvesting And Reusing Beer Yeast

Learning how to harvest, wash, and reuse your beer yeast is a neat skill that gets you one step closer to making beer the way the pros do. Besides, washing and reusing beer yeast can help you save a few bucks so you can get those homebrewing gadgets you’ve always wanted.

Learning how to harvest, wash, and reuse your beer yeast is a neat skill that gets you one step closer to making beer the way the pros do. Besides, washing and reusing beer yeast can help you save a few bucks so you can get those homebrewing gadgets you’ve always wanted.

A few important things to consider before reusing your beer yeast:

- When harvesting beer yeast, sanitation is very important! When you practice good sanitation, you can reuse yeast for ten generations or more!

- Yeast should be harvested from a clean and healthy fermentation. Take notes on how your batch turns out. If the beer didn’t come out well, you probably don’t want to reuse the beer yeast.

- Consider the color of the beer you’re harvesting yeast from. Yeast harvested from a dark beer and pitched into a lighter beer will likely affect the color of your beer, so try to pitch yeast from light beer to a dark one.

- Just like with color, think about the hoppiness of the beer you’re harvesting yeast from. A yeast slurry from a very hoppy beer may affect the bitterness of your beer.

Now, here’s an easy step-by-step guide to harvesting and washing beer yeast. Follow these steps when reusing beer yeast and you’ll have not problems, whatsoever:

- The night before transferring your beer from primary to secondary fermentation, boil a half gallon of water for 20 minutes to sterilize it. Carefully pour the water into a sanitized jar or growler, seal it with a sanitized lid, and place the growler in the refrigerator to cool overnight.

- The day of the transfer, clean and sanitize several (four or more) glass jars and lids. Remove the growler of cool water from the fridge.

- After transferring to secondary, pour half of the water from the growler onto the yeast cake left behind in the primary fermenter. Swirl the water around to stir up the beer yeast and let sit for several minutes. The slurry will stratify into three layers: watery beer mixture on top, dead yeast and trub on the bottom, and healthy yeast in the middle.

- Pour off and discard the watery top layer. Then pour the healthy beer yeast slurry into half of your glass jars, taking care to leave the darker yeast slurry at the bottom of the fermenter. Allow these jars to sit for several minutes.

In ten minutes or so, the slurry will separate. Just like before, pour off and discard the watery stuff on top, then pour the white yeast slurry into the remaining jars, leaving behind the darkest part of the slurry.

In ten minutes or so, the slurry will separate. Just like before, pour off and discard the watery stuff on top, then pour the white yeast slurry into the remaining jars, leaving behind the darkest part of the slurry.

- Place the lids on the jars of washed yeast and place in the refrigerator. Don’t forget to label the jars!

- Use the harvested beer yeast within a few months, the sooner the better, and prepare a yeast starter to ensure optimal viability for your next batch.

Have you ever tried reusing beer yeast from a slurry or cake? Did you end up with more beer yeast than you can use? Yes, you can make bread with it!

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

Alternative Techniques For Adding Hops To Beer

Hops – they’re the defining ingredient in many styles of both craft and homebrewed beer. From brown ales to stouts to IPAs, there’s hardly a beer out there that isn’t made with the addition of hops.

the defining ingredient in many styles of both craft and homebrewed beer. From brown ales to stouts to IPAs, there’s hardly a beer out there that isn’t made with the addition of hops.

You may be aware that adding hops to beer at different points of the boil contribute different characteristics to the finished beer. Hops added early to the boiling wort are responsible for most of the bitterness in the beer, while hops added later to the boil contribute more of the floral, spicy, piney, or citrusy flavor and aroma qualities that hopheads know and love.

If you are following a beer recipe it is customary for it to state the boiling times for the various hop additions, whether it be: 60, 30, 15 or 5 minutes. Just following these times for standard hop additions.

But besides these standard hop additions through out the wort boil, there are a few alternative techniques for adding hops to beer that you may want to have in your homebrewing tool box:

- First wort hops – First wort hopping involves adding hops while collecting the runnings from an all-grain mash. Simply take the hops that you would add at the end of the boil and place them in the brew kettle as you collect the wort pre-boil. Some brewers believe that this technique results in “a more refined hop aroma, a more uniform bitterness, and a more harmonious beer overall.”

- Dry hop – Dry hopping is the practice of adding hops to the secondary fermenter while the beer is conditioning. This is another technique which adds additional aroma to the beer. As with first wort hopping, low alpha acid aroma hops are best suited for dry hopping. Use a screen, mesh hop bag, or cold crash your beer to separate the hops from the finished beer.

- Hop back – This is a method of adding hops to beer that is a little bit more involved. A hop back is a piece of equipment used to recirculate beer through the hops packed into it. For Sierra Nevada,

it’s called a torpedo (hence “Torpedo” IPA), and for Dogfish Head it’s called Randal the Enamel Animal. If you’re a do-it-yourself-er, you can build your own hop back using a stainless steel container and standard hardware store fittings.

it’s called a torpedo (hence “Torpedo” IPA), and for Dogfish Head it’s called Randal the Enamel Animal. If you’re a do-it-yourself-er, you can build your own hop back using a stainless steel container and standard hardware store fittings.

- Foosball table – If you’re a fan of the Dogfish Head IPAs, you’ve probably heard why they’re named 60-Minute, 90-Minute, and 120-Minute. Founder Sam Calagione originally used a jury-rigged foosball table for adding hops gradually throughout the 60-, 90-, or 120-minute boil. The idea is that this “continual hopping” results in a more rounded hop profile. While that may be true, this example highlights how creative ideas can be applied to the brewing process. Don’t be afraid to try out some techniques of your own!

What’s your “go-to” technique for adding hops to beer? Please share in the comments below!

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder and editor of the Local Beer Blog.

Back Sweetening Wine After Fermentation Or Before Bottling

Is it ok to back sweeten a wine right after the fermentation or should I wait?

Is it ok to back sweeten a wine right after the fermentation or should I wait?

Thank,

Terry

—–

Hello Terry,

Before back sweetening a wine, it is important that you wait until the fermentation has completed. It is also just also important that the wine have plenty of time to settle out all the yeast. Most often, the yeast has not had time to do this by the time you do your second racking. So, normally you will not want to back sweeten your wine right after the fermentation.

In reality, the best time to back sweeten a wine is right before bottling. This gives plenty of time for the wine to clear up. There is no upside to sweetening the wine sooner than this, only a potential for problems.

The reason clearing the wine is so important is because the wine be in a stable state before sweetening, otherwise all the new sugars that are added will end up as fodder for a renewed fermentation.

Cloudiness in a wine usually indicates it still has excessive wine yeast. The wine yeast is as fine as flour and settles out the slowest, so it is that last thing to be suspended in the wine. It is very hard to stabilize a wine that has residual wine yeast still floating throughout the wine.

The wine stabilizer, potassium sorbate, is what has to be used to stabilize a wine when back sweetening a wine. While a sulfite such as sodium metabisulfite or Campden tablets should be used as well, all of this is still not enough to completely stabilize the wine if too much residual yeast is still in the wine.

Potassium sorbate stabilizes a wine in an entirely different way than these two sulfites. It does so by putting a restrictive coating on the outside surface of each of the few remaining yeast cells. This does not kill or destroy the yeast. They will die on their own in hours or days. But it makes them unable to reproduce themselves. The ability to reproduce is the real threat that can manifest into a full-blown fermentation.

Potassium sorbate stabilizes a wine in an entirely different way than these two sulfites. It does so by putting a restrictive coating on the outside surface of each of the few remaining yeast cells. This does not kill or destroy the yeast. They will die on their own in hours or days. But it makes them unable to reproduce themselves. The ability to reproduce is the real threat that can manifest into a full-blown fermentation.

If the wine is still even slightly, visually cloudy, there may not be enough potassium sorbate to go around to do a complete coat all the yeast cells. This is the downside to back sweetening the wine sooner then necessary.

In a nutshell, don’t back sweeten your wine right after fermentation. Give it plenty of time to clear, then back sweeten. And if convenient, don’t even think about back sweeten you wine until right before bottling.

Happy Wine Making,

Ed Kraus

—–

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

Adding More Grape Concentrate To Wine

I am getting ready to make 10 gallons of wine from 2 cans of Sun Cal Johannisberg Riesling concentrate. My question is would an additional can of Sun Cal Riesling really improve the fullness of the wine or would not really be worth the investment of shipping another can of concentrate? I have made a batch of this wine several years ago and it turn out pretty good. Hope you can help…

I am getting ready to make 10 gallons of wine from 2 cans of Sun Cal Johannisberg Riesling concentrate. My question is would an additional can of Sun Cal Riesling really improve the fullness of the wine or would not really be worth the investment of shipping another can of concentrate? I have made a batch of this wine several years ago and it turn out pretty good. Hope you can help…

Name: Vincent O.

State: IA

—–

Hello Vincent,

Thanks you for this interesting question.

[To catch up other readers, Sun Cal concentrated grape juices come in 46 fl. oz. cans. Each can makes 5 gallons of wine when you follow the directions. Along with the can, sugar, acid blend, tannin, yeast nutrient and yeast are added to make up the wine recipe. Vincent, wants to push the envelop a little by adding more grape concentrate to his wine. He’s making a double batch, 2 cans to 10 gallons. He’s thinking about adding a third can.]

Without question, adding a third can would bring up the body and flavor of the wine, but the perceived impression of the resulting wine would not be one with 50% more flavor and body. Adding more grape concentrate to the wine would only intensify the wine’s flavor only marginally.

This is because of the way us humans tend to perceive things. All of our senses do not react on an even scale. For example, two jet engines side-by-side are not twice as loud as one. If you double the wattage of a light bulb, it does not seem twice as bright. If you add 50% more concentrate to your wine recipe, it will not seem like 50% more flavor.

I’m not saying that adding more grape concentrate to the wine is not a good idea, I’m just letting you know what to expect if you do decide to add more. Whether you feel it would be worth it is completely up to you. You can expect more flavor and body, but it will not be 50% more.

We’ve had many customers over the years that have used 2, and even, 3 cans of Sun Cal concentrate to just 5 gallons and loved the resulting wine.

Another important aspect to this that needs to be addressed is that if you do decide to add more grape concentrate to your wine, you will need to compensate by adding less sugar and less acid blend to the wine recipe. This is because the additional can of grape concentrate is adding both more sugar and more fruit acid.

Regardless, of how much flavor you are trying to get, the sugar level and acid level should always remain the same. The beginning sugar level determines how much alcohol the resulting wine will have. The acid level of the wine controls how tart or sharp the wine will be.

Keeping both of these at their proper level is relatively easy. You will need to use a hydrometer to add the proper amount of sugar. Keep dissolving sugar into wine must until the hydrometer gives you a reading on the potential alcohol scale of 10% or 11%.

An acid test kit will be needed to know how much acid blend to add to the wine recipe for proper taste. An acid test kit is a valuable tool for controlling any wine’s acidity. After taking a reading the directions will show you how to determine how much acid blend to add.

Adding more grape concentrate to wine is something that is pretty simple to do. Plus, it’s away fun to experiment. That’s half the fun of making your own wine. You have the opportunity to make your own personal creations.

Happy Winemaking!

Liquid Beer Yeast vs Dry Beer Yeast For Homebrewing

Guest beer blogger, Heather Erickson, shares some of her tips and insights about liquid and dry beer yeast.

Guest beer blogger, Heather Erickson, shares some of her tips and insights about liquid and dry beer yeast.

————————————————-

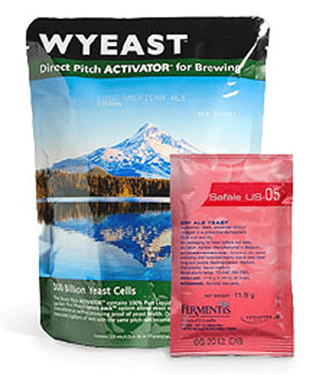

When I first got into homebrewing, I was introduced to the Wyeast Smack Pack. This is a pouch of liquid yeast that has within it another pouch of activator that can be busted open by smacking it.

I can’t lie, it was kind of fun smacking that direct beer yeast activator and watching those little yeasties start working. Over the years, I have experimented with dry beer yeast and well, I’m torn between the results. Below are some of the pros and cons of liquid beer yeast vs dry beer yeast.

- Pro: Liquid beer yeast offers variety

With Wyeast offering over 50 different beer yeast strains for homebrewing, variety is quite possibly the spice of life with liquid yeasts. From a Belgian Strong Ale to a good ole American Ale, the variety of liquid beer yeast strains seem pretty endless. Besides the everyday ale/lager yeasts, liquid yeast varieties also include seasonal offerings.

- Pro: Dry beer yeast keeps longer

As a once a month home brewer, I find myself in two scenarios: either I am scrambling for brewing ingredients the day of, or I am crossing my fingers that my beer yeast is still healthy. The dry yeast alternative negates that second worry. Staying fresh for up to two years in the refrigerator, a dry yeast option like Fermentis Safale US-05 is a high-performing alternative to my usual go-to liquid beer yeast smack pack.

- Con: Liquid yeast is more expensive

If we are just looking at the numbers, on average, a liquid beer yeast pouch is about twice as much, if not more, than a packet of dry beer yeast. While cost might not be a concern if you prefer a certain type of flavor that a beer yeast provides, the economics are still worth noting.

- Con: You won’t know if your dry beer yeast is healthy unless you rehydrate

Rehydrating dry beer yeast prior to pitching seems to be a point of contention among homebrewers. While some believe this step is necessary to ensure healthy yeast cells, others feel that it isn’t. Even dry yeast manufacturers are torn on the topic. A dry beer yeast packet boasts anywhere from 200-300 billion yeast cells, compared to 100 billion in liquid yeast. Pitching the dry yeast straight into your fermenter without rehydration could end up killing some of those cells, up to 50% or so. Taking that into account, the number of cells in both liquid beer yeast and dry beer yeast would end up being just about equal.

Besides water, yeast is arguably the most important ingredient in beer. Without it, you just have sugar water. That’s why there has always been such a big debate about using liquid beer yeast vs dry beer yeast for homebrewing your beer. It’s an important piece of the brewing puzzle.

My advice? Test out your tried and true Pale Ale recipe with a Wyeast 1056 and a Fermentis Safale US-05. Whichever pint you prefer is the yeast you should use.

Happy brewing!

—–

Heather Erickson is a homebrewer with three years experience and has competed in the GABF Pro-Am Competition. She writes the blog This Girl Brews and is a regular contributor to homebrewing sites. Find her on Twitter at @thisgirlbrews.

Special Interview: Dan Bies Of Briess Malt

Today we have an extra special guest! In this exclusive interview, Dan Bies of Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. shares his tips for brewing with Briess malts and malt extracts, as well as some insights into the Briess product development process. This is great information for brewers of all levels! We hope you enjoy!

Today we have an extra special guest! In this exclusive interview, Dan Bies of Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. shares his tips for brewing with Briess malts and malt extracts, as well as some insights into the Briess product development process. This is great information for brewers of all levels! We hope you enjoy!

Dan works in the technical service department at Briess. He is their pilot brewer which essentially means he gets to have a lot of fun doing test batches of beer with vast array of products that Briess has to offer.

1. Hi Dan, thanks for taking the time to share your expertise with us today. For starters, can you tell us how you came to work with Briess, how long you’ve been with the company, and what you do there?

The day I started working in the Briess malt analysis lab is the day I became determined to start home brewing. I’ve been at Briess for six years now and my current position is as a Pilot Brewer, Technical Services Representative, and QA Chemist. I help to commercialize new extract products and assist customers with application-related questions on our existing products. I also do recipe and finished product development on a variety of beverages including beer, Malta, and Flavored Malt beverages.

2. Part of the fun of home brewing is developing your own recipes. Can you share with us some of things you think about in terms of malt and malt extract when developing a new beer recipe?

When formulating with malt and extract my first consideration is a target style. Once I have this I try to think of what is traditionally used in its formulation and what attributes the ingredients bring to the character of the beer. Next I consider possible substitutions; this usually results in chewing on malts and making malt teas. Lastly, I brew. I typically use extract and grain interchangeably, but I almost always find myself steeping additional grain into extract brews.

When formulating with malt and extract my first consideration is a target style. Once I have this I try to think of what is traditionally used in its formulation and what attributes the ingredients bring to the character of the beer. Next I consider possible substitutions; this usually results in chewing on malts and making malt teas. Lastly, I brew. I typically use extract and grain interchangeably, but I almost always find myself steeping additional grain into extract brews.

3. What are some of the main differences between wort made from extract and wort made from grain? How do these products differ in the their effects on the final beer? Are there any additives in malt extract?

There’s almost no difference when using extracts Briess makes. We brew all of our malt extracts from the same Briess malts used by breweries and home brewers, using traditional brewing techniques in a 500-barrel brewery. By the way, it’s the second largest brewhouse in Wisconsin. Malt and water, that’s all that goes into our extracts. Absolutely no additives are used. Plus, all of our extracts are made using specialty malts to achieve full color and flavor. Some malt extract producers use the boil to develop color and flavor.

Extract brewers who use Briess extracts can achieve the same results as an all grain brewer, however they must take care in choosing their ingredients. Liquid malt extracts will develop color and some flavor if they’re not stored properly and exposed to heat. Time can do the same thing, but heat is the worst offender. So it’s really important that malt extracts are properly stored from the time they leave the Briess warehouse. Using the freshest possible liquid malt extract from a reliable distributor is key. You can tell the date a Briess malt extract was produced by reading the lot code. For example, 130521 would be May 21, 2013. The first two digits indicate the year, the middle two the month and the last two the date of production.

If you’re not sure of the freshness we recommend that you use dry extracts. These do not darken or develop flavor defects over time because the products are simply too dry for the negative reactions to occur.

4. Have you found a ratio of malt extract to grain that works well for you?

Depends on style and desired character. Not all Briess malts are showcased in the CBW® [Brewers Grade Malt Extracts] line. If I ever want to go heavy on specialty malts, but don’t have time for all-grain, I will formulate with specialty malts to match a flavor and color target, steep the malt, then add the remaining fermentables with a light malt extract. I feel that almost any style can be made with a large inclusion of light malt extract and steeped grains. A small amount of Munich 10 or Bonlander® Munich Malt steeped with Pilsen Light extract is a great substitute for Pale Ale Malt.

5. OK, now let’s switch gears and talk a little about product development. I’ve noticed that Briess releases a new variety of malt from time to time. How does Briess go about developing a new malt or malt extract product? What is that process like?

When we determine a new malt or malt extract we would like to add to our standard product list, the first thing we do is bring in all competitor products of the same or similar style. Then we conduct blind sensory, analyze the results and decide the target flavor, color and other attributes it should have. Then we produce pilot batches until the target product is met. Some of the recent introductions only took one try. Then a second blind sensory is held to see how our new malt fits into the category. That process is repeated, if necessary, until we are entirely happy with the results. Then we make several productions, use the new malt or extract in our pilot brewery, develop recipes that showcase it, and then brew at a number of breweries before officially releasing it. Our sensory panel includes our maltsters, brewers, experienced GABF judges, food scientists trained in sensory analysis, and other staff members.

6. Are there any new products in the pipeline you’d like to share with us?

6. Are there any new products in the pipeline you’d like to share with us?

We recently started producing a high maltose yellow corn syrup for use in gluten-free beers and food. Produced from corn grits, this product is the equivalent of the wort brewers would get if they used corn in their brews; however, it is in a convenient liquid form. This makes brewing with this popular grain easy and avoids the needs for long separate grain cooking and boiling cycles. Because it’s made from grain and unrefined, this type of corn syrup has a pleasing corn flavor, yellow color and some of the vitamins and nutrients needed for yeast nutrition. We made this syrup using Organic Corn so it is all-natural and non-GMO.

Did you enjoy this post? Please take a moment to share it on your favorite social network! Thanks and cheers!

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He is a graduate of the Oskar Blues Brew School in Brevard, NC, and founder of the Local Beer Blog.

The Anatomy Of A Hop Cone

Prized by brewers far and wide for its bittering, flavor, and aroma qualities, the hop is an integral part of beer. But what is a hop? What’s inside the hops? What’s the anatomy of a hop cone?

Prized by brewers far and wide for its bittering, flavor, and aroma qualities, the hop is an integral part of beer. But what is a hop? What’s inside the hops? What’s the anatomy of a hop cone?

Hops come from a perennial plant called Humulus lupulus (lupulus as in wolf, so named for the voraciousness of the plant’s growth), which sends vines up from a rhizome in the ground. These vines (a.k.a. bines) have been known to climb to 20 feet or higher in a commercial hop field. Hops, the part of the plant used in brewing, are the flowers of the plant. It is the hop flowers’ essential oils and resins that make it so valuable as a beer brewing ingredient.

A hop flower looks like a miniature green pine cone. The resins, commonly referred to as alpha acids, are contained at the base of the hop cone in the lupulin glands. When boiled, these alpha acids are isomerized, a quick shift in molecular structure that makes them soluble in wort.

The alpha acids are what make beer bitter. A simple calculation allows brewers to figure out the IBUs (international bittering units) of their beer and compare their beer to others using a universally accepted scale. The two primary chemicals within the alpha acids are called humulone and cohumulone.

But also within the anatomy of a hop cone are other components that contribute to flavor and aroma. These characteristics are derived from hop oils. Because they’re more delicate than the alpha acids, the hop oils will evaporate if they’re boiled for too long. For this reason, they’re added to the wort late in the boil or afterwards. Commercial brewers may use a hop back, but homebrewers will usually put the hops directly in the secondary fermenter (this practice is called dry hopping).

There are several different types of essential oils within the hop cone, each contributing different flavor and aroma characteristics:

- Myrcene – floral, citrus, and piney

- Humulene – spicy, herbal, European

- Caryophyllene – herbal, European

- Farnesene & other oils

(If you’re interested, Ray Daniels’ book, Designing Great Beers, is a great source for more info on the different hop oils.)

After being harvested from the hop plant, hop cones are usually processed into pellets. Specialized machinery removes the extraneous vegetative material, preserving the resins and oils. The processing results in higher hops utilization (a measure of how many alpha acids are dissolved in the wort) and makes for easier storage. Some brewers, like Sierra Nevada, still use whole hops, but hop pellets have become the industry standard.

When buying hops for home brewing, fresher is always better (unless brewing a lambic, which is made with aged hops). It’s best to purchase your hops right before you use them. If you will be using the hops within a few days, store them sealed in a plastic bag in the refrigerator. Otherwise, keep them in the freezer, preferably vacuum-sealed, until you’re ready to brew.

This is the basic anatomy of a hop cone and why it is used in beer. Here’s where you can find more information about hops: (Nearly) Everything You Need To Know About Hops.

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He is a graduate of the Oskar Blues Brew School in Brevard, NC and founder of the Local Beer Blog.