When making my wine I have never topped up on the first or second racking. I have had great results but a few people tell me I need to be topping up the wine. I could see topping up the wine if I was batch aging, but for the 4 weeks I hold and rack after primary fermentation I am no so sure. It should be mentioned I am usually only down much less than a liter. Your thoughts?

When making my wine I have never topped up on the first or second racking. I have had great results but a few people tell me I need to be topping up the wine. I could see topping up the wine if I was batch aging, but for the 4 weeks I hold and rack after primary fermentation I am no so sure. It should be mentioned I am usually only down much less than a liter. Your thoughts?

Name: Mike in B’ville

State: NY

—–

Hello MIke,

If you are making wine from a box wine ingredient kit topping up the wine is not recommend. Partially for the reasons you gave about it not being that long of time, but also because these kit manufacturers produce the wine in such a way that they do not oxidize very easily. This is just one of the many advantages of using a wine ingredient kit.

However, if you are making a wine from fresh fruit or fresh juice the story is a little different.

First off, you don’t need to be topping up the wine while the fermentation is occurring. This is because the CO2 gas (carbon dioxide) coming off the fermentation keeps the air away and protects it from oxidation. The CO2 is slightly heavier than air, so it wants to create a protective blanket across the surface of the wine.

Even when the fermentation has completely stopped, as long as you have not taken the air-lock off the fermenter, there is no reason to be topping up the wine. The CO2 gasses from the fermentation are still trapped in the head-space of the fermenter. No air is in the head-space.

But the moment you remove the air-lock or take the lid off the fermenter, all the rules change. You are then in a situation where not only is topping up important but vital to the color and flavor of the wine.

What is topping up a wine?

What is meant by topping up a wine is increasing the volume of the wine so as to reduce the amount of head-space in the vessel. To be more specific, the exact goal here is to eliminate as much surface contact between the wine and the air. You want this contact to be as minimal as possible.

In the case of a carboy, when you increase the volume of the wine you push the surface of the wine from the shoulders into the neck. It goes from maybe a square foot of surface contact area to maybe 2 square inches.

Hope this info helps you out,

Ed Kraus

———————————————————————————————————

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

How Much Does It Cost To Make Your Own Beer?

Many homebrew retailers will tell you that you can save money by homebrewing. But is this really the case? How much does it really cost to make your own beer? Let’s crunch some numbers.

Many homebrew retailers will tell you that you can save money by homebrewing. But is this really the case? How much does it really cost to make your own beer? Let’s crunch some numbers.

The typical homebrewer brews enough beer to produce about five gallons. Account for some loss, and let’s call it eight six-packs. That’s a lot of beer! What does it cost to buy a six-pack of a typical pale ale? It varies depending on the brand and the retailer, but let’s call it $10, or $80 for eight six-packs. Maybe less if you buy a twelve-pack here and there. Depending on your state, tax can add a nice chunk too.

A pale ale recipe kit on the other hand, such as the Steam Freak “Bazz” Pale Ale, costs just shy of $35. Of course there’s shipping to account for, but buy two or more and the price goes down to under $32 per kit, plus you qualify for E. C. Kraus free shipping. Now we’re talking! As you can see it really doesn’t cost that much to make your own beer.

Shop smart and you could be in for some serious savings over buying your beer from the store. Compare it to the amount you’d spend at the local pub…you can save a lot by homebrewing!

The challenge comes in when we start adding in the variables, such as equipment. Our Beer Makers Necessities Kit runs for just shy of $130, but includes your first ingredient kit and free shipping. It’s an up front investment, so the more your brew, the less it costs per batch. There are other costs that are spread out over time, such as cleaner and sanitizer, but their per-six-pack cost is pretty minimal (at most a dollar or so per gallon of beer).

Beer blogger Bryan Roth (who you may remember from his guest post titled Malt, Hops, and Zen) explores this question on his personal blog, This is Why I’m Drunk. He was kind enough to compile some data on the costs of his beer recipes and then compare them to their commercial equivalent:

Bryan’s Homebrew Ingredient Costs

|

Beer (K) = Prepared Kit (R) = My Recipe |

Ingredient Cost |

Cost per Bottle |

Cost per Six-Pack |

ABV |

|

Jalapeno Blonde (K) |

$30 |

71 cents |

$4.26 |

6.50% |

|

Bass Ale Clone (K) |

$33 |

79 cents |

$4.74 |

5% |

|

Belgian Saison (K) |

$39 |

93 cents |

$5.58 |

6% |

|

Beer/Cider Hybrid (K) |

$40 |

95 cents |

$5.70 |

7.30% |

|

Poor Richard’s Ale (R) |

$45 |

$1.07 |

$6.42 |

5.50% |

|

Apricot Wheat (K) |

$47 |

$1.12 |

$6.72 |

6% |

|

Blueberry Wheat (R) |

$48 |

$1.14 |

$6.84 |

6.50% |

|

Honey Basil Ale (R) |

$48 |

$1.14 |

$6.84 |

7% |

|

Imperial IPA (R) |

$63 |

$1.50 |

$9.00 |

9.20% |

|

Watermelon wheat (R)* |

$65 |

$1.30* |

$7.80 |

7% |

|

Double IPA w/ honey (K) |

$66 |

$1.57 |

$9.42 |

8% |

Bryan’s Homebrew Costs vs. Commercial Equivalent

|

Bryan’s Beer per Six Pack |

Commercial Beer per Six Pack |

Price Difference |

|

Bass Ale Clone – $4.74 |

Bass Ale – $8 |

-$3.26 |

|

Apricot Wheat – $6.72 |

Magic Hat #9 – $8 |

-$1.28 |

|

Blueberry Wheat – $6.72 |

Sea Dog Blueberry – $9 |

-$2.28 |

|

Honey Basil Ale – $6.84 |

Bison Organic Honey |

-$2.16 |

|

Watermelon Wheat – $7.80 |

21st Amendment Hell or High Watermelon – $9 |

-$1.20 |

—————————————————————————————————–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder and editor of the Local Beer Blog.

7 Confessions Of A Homebrewer

Have you ever brewed a beer that you weren’t proud of? Has your home been taken over by brewing gear, kegs, and bottles? While homebrewers are a proud bunch, there are some aspects of the hobby that we wouldn’t go out of our way to share with just anyone.

Have you ever brewed a beer that you weren’t proud of? Has your home been taken over by brewing gear, kegs, and bottles? While homebrewers are a proud bunch, there are some aspects of the hobby that we wouldn’t go out of our way to share with just anyone.

At the risk of hurting my street cred (who doesn’t love a little self-deprecation?), here are a few of the “trade secrets” I normally don’t let out of the bag. Can you relate to any of these?

- My bathtub is used for brewing more often than bathing. Some call us “bathtub brewers,” but I don’t know anyone who would actually make beer in the tub. It just comes in handy for cleaning and sanitizing and as a staging area for bottles and fermenters in various stages of cleanliness. However, if my girlfriend wants to take a bath, it means I have to move all my brewing equipment out of the way.

- Our coat closet is actually a fermentation chamber. Yes, we tend to have more fermenters bubbling than coats hanging at any given time. But who needs a rain jacket when you have beer?

- I once made a batch that tasted a little funky…but I still drank every bit of it. It happens to everyone at least once. For some reason, a batch comes out tasting pretty far from what you expected. Luckily, there are no known pathogens that can survive in homebrew, so if you can stand the taste, bottoms up. The fun part is that we learn from our mistakes, and every subsequent beer is that much better!

- A significant portion of my disposable income goes towards homebrewing. What can I say? I love to brew. You can see where my priorities lie.

That’s enough self-humiliation for now. To repair my damaged ego, I asked some fellow brewers to contribute skeletons from their own homebrewing closets:

- I stained my garage floor when bottling and moved boxes over it so my wife wouldn’t find out. -Anonymous

- My wife and I have a delicate balance of understanding when it comes to homebrew, so asking for any extra space for bottles or equipment can be a challenge. So, I’ve had to improvise… I have two dedicated spaces for fermentation, courtesy of tough negotiations with my wife: half of a downstairs closet for primary/secondary and half of an upstairs closet for bottle conditioning. I was very ambitious my first year of homebrewing and made 13 batches, which meant a lot of bottles. When I ran out of space, I had to hide some bottle conditioning beer in the one thing scattered throughout the house that was plentiful — my wife’s vast shoe collection. -Bryan Roth, This Is Why I’m Drunk, @BryanDRoth

- My guest bedroom has a kegerator — though I must say, guests rarely complain when I make that confession. -Thom O’hearn, @AVLBeerScout

Do you have any embarrassing stories from your homebrew experience? Share in the comments!

——————————————————————————————————-

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

Adding Campden Tablets To Cider

I’ve read that you have to add a campden tablet to cider 24 hours before you add the yeast…..I’ve not done this and my cider is now fermenting away. Can I add the correct amount of tablets per gallon once I have strained the sediment off – 2/3 times – 24 hours before I bottle the cider…….am worried that the cider will not be safe to drink!

I’ve read that you have to add a campden tablet to cider 24 hours before you add the yeast…..I’ve not done this and my cider is now fermenting away. Can I add the correct amount of tablets per gallon once I have strained the sediment off – 2/3 times – 24 hours before I bottle the cider…….am worried that the cider will not be safe to drink!

Name: Fiona

State: Nova Scotia

—–

Hello Fiona,

You didn’t add Campden tablets to the cider, and that’s okay. Since your fermentation is active, the cider should be fine. The fact that it is active means that the cider yeast has successfully multiplied into a full colony and will be able to protect the cider from the growth of any mold or bacteria that may be in the juice.

The reason Campden tablets are called for in a cider recipe before adding yeast is to destroy any trace amounts of mold spores or bacteria that may be in the juice. Any small amounts can multiply into a full-blown spoilage if the yeast doesn’t happen to grow and take over the juice first.

In your case the yeast did take over, so spoilage did not have any chance to take place — no harm, no foul.

I would like to point out that when you do add Campden tablets to cider before a fermentation, it is important that you wait 24 hours before adding the yeast. And, it is important that the cider not be sealed up during the 24 hours. Just cover it with a thin towel. This is because the gas from the Campden tablets need to escape from the cider before you add the yeast, otherwise the Campden tablets can destroy some of the yeast in the cider, as well.

This is not the only time you add Campden tablets to the cider, either. You should add them again after the fermentation has completed (the should be verified with a hydrometer). And, you should also add Campden tablets to the cider, again, right before bottling.

Also, please realize that if you plan to back sweeten the cider, the Campden tablets will not eliminate a chance of a re-fermentation in the bottle. For this you will need to also add potassium sorbate along with the Campden tablets.

Happy Winemaking,

Ed Kraus

———————————————————————————————————–

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

Making Wine From Grapes At Home

Can you furnish a grape wine recipe for 5 gallons of Cynthiana grape wine?

Can you furnish a grape wine recipe for 5 gallons of Cynthiana grape wine?

Name: Dennis T.

State: GA

Hello Dennis,

Making wine from grapes is more of a process than a recipe. This is true regardless if you are a winery or just an individual making grape wine at home. It’s different than making wine from a fruits like blueberries or peaches where you can follow a wine recipe to make the wine.

The primary reason for this difference is that when you are making wine from grapes you are using 100% grape juice. No water is being add to the grape juice. This means that a change in sweetness or acidity from one season to the next affects what’s needed in the grape wine recipe, dramatically.

This is not so much the case when making a batch of raspberry wine, for example. The actual raspberry juice may only represent about a fifth of the liquid that’s in the wine. The rest is water, so the amount of ingredients such as Acid Blend, sugar, etc. are somewhat predictable, regardless of how sweet or acidic the raspberries are. These amounts can be packaged up neatly and put into a wine recipe.

So what does this mean for the person making wine from grapes at home? It means that they will need to test the grapes they have at hand to know how much of the wine ingredients to add.

Some wine ingredients will be constant regardless of the grapes. This applies to yeast nutrient, pectic enzyme, potassium metabisulfite and wine yeast. With each of these items simply follow the amounts called for on the containers they came in.

But with sugar, Acid Blend and wine tannin, the amounts will vary based on tests you will give the grape juice. For sugar you will take a hydrometer reading; for Acid Blend you will take an acid test reading; and for tannin you will take a litmus reading with pH papers.

Dennis, we have a great article on our website that covers making wine with grapes. This info will help you to add the correct wine ingredients in the correct amounts so that you can come up with the best Cynthiana grape wine possible.

Happy Winemaking,

Ed Kraus

———————————————————————————————————–

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

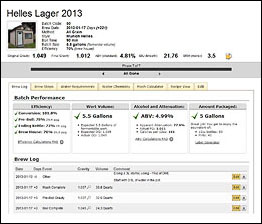

Taking Advantage Of Beer Brewing Stats And Calculators

Today’s guest post is from Larry of Brewer’s Friend. He shares some insights on how to improve your home brewing calculations.

Today’s guest post is from Larry of Brewer’s Friend. He shares some insights on how to improve your home brewing calculations.

————————————————

The science of brewing can be just as alluring as the smells, tastes, and never ending equipment accumulation related to home brewing. Brewing science is a wide topic that includes everything from yeast growth, to hops analysis, to the various brewing processes.

Let’s start at the beginning: the science and stats behind beer recipes. Beer recipes have several stats including original gravity, final gravity, IBUs (bitterness), SRM (color), and ABV (alcohol content).

A quick walk through of the stats:

- Original Gravity (OG) – Original gravity tells how much sugar is in the wort prior to fermentation. This is based on how much grain was used, what the volume of the batch is, and mash efficiency (for all grain brewers). This is where the term ‘high gravity beer’ comes from. The higher the OG the higher the alcohol potential. There are two popular gravity scales used in brewing, specific gravity and degrees Plato. Specific gravity (1.xxx) is popular in the home brewing world. Plato is generally used by pro brewers and works well with the metric system.

- Final Gravity (FG) – Final gravity tells how much sugar the wort contains after fermentation. FG depends on the fermentability of the wort and the yeast strain selected. Other factors like temperature, yeast health, alcohol level, and mash temperature also impact the FG. The FG is the gravity of the completely fermented beer.

- Alcohol by Volume (ABV) – ABV is calculated using the difference between the OG and FG. The higher the OG and the lower the FG, the more alcohol is in the beer.

- International Bittering Units (IBUs) – IBUs indicate how bitter a beer is. Perceived bitterness can be different from the raw IBU number. A malty beer at 60 IBUs compared to a thin dry beer at 40 IBUs may appear to have equal bitterness.

- Standard Reference Measure (SRM) – SRM is the color the beer is expected to be given the grains used. Base grains like 2-row and pilsner impart straw/golden colors. Caramel grains add red, copper, and brown hues. Roasted grains impart dark brown and black color.

Beer recipe software can be used to calculate all of these numbers:

Brewer’s Friend has set of over 20 basic calculators, plus a fully integrated recipe editor.

Taking measurements:

For taking gravity readings (the OG and FG) a hydrometer or refractometer is used. I find both work well as an essential tool for record keeping, but prefer hydrometers for their economy and consistent accuracy. Refractometers can be a little finicky at times in terms of accuracy, but they only require a drop or two of wort vs. a few ounces with hydrometer readings.

Don’t forget to pickup a graduated cylinder to hold the hydrometer sample!

Note: Hydrometer readings must be temperature corrected, since gravity density changes with temperature. Hydrometers are usually calibrated to 60F or 68F. Brewer’s Friend has a hydrometer temperature correction calculator that comes in handy. This way, even if your sample is still at a warm 100F, you can get a good idea of what the actual value is before it cools down.

Refractometer readings are given in Brix (which is effectively the same as Plato), but many home brewers work in specific gravity. Our refractometer calculator automatically handles this conversion, and accounts for the optional correction factor that some refractometers require.

Unfortunately there is no simple gadget to measure IBUs. The process is quite complex and requires a beer sample to be sent to a lab for analysis. Someday, maybe we’ll see a Kickstarter project that delivers IBU measurements in a hand held device?!

Recording your measurements:

Recording your measurements:

Brewer’s Friend supports a brew feature that allows log entries for tasting notes, dates, and most importantly gravity and volume measurements. The log entries are used to calculate the batch’s actual ABV, efficiency, attenuation, and other stats so brewers know how their beer really turned out in comparison to a planned recipe.

Other important beer recipe calculations:

- One way to take your brewing to the next level is to pitch yeast at the pro rates. This usually involves making a starter from a smack pack or vial. Brewer’s Friend has an easy to use yeast pitch calculator, which makes sure you pitch the right amount of yeast for your beer.

- Water chemistry is also important in brewing. I pay close attention to my ion levels in every brew. Brewer’s Friend has two water chemistry calculators. The first is a basic version targeted at hitting water ion levels for style and taste. The second water chemistry calculator is an advanced version meant for use by all grain brewers, and gives a prediction of mash pH among many other little details. The backend to our advanced calculator was written by Kaiser of Braukaiser.com.

The team behind Brewer’s Friend is a group of highly dedicated and experienced brewers, bloggers, and technologists whose mission is to make your brewing the best it can be. Check out our website for all your brewing calculation needs and don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions!

Cheers!

Guest post by Larry at Brewer’s Friend

https://www.brewersfriend.com

Making Wine With Eating Grapes

Our local supermarket has grapes on sale, with and without seeds. Can I crush these to make wine?

Our local supermarket has grapes on sale, with and without seeds. Can I crush these to make wine?

Name: John

State: New York

Hello John,

Yes, you can make wine with eating grapes, but realize they are not intended for making wine.

They have been bred for eating. This means that the sweetness and acidity are both lower than what you’d expect from an actual wine grape. The flesh is thicker and firmer with an eating grape than that of a wine making grape. People like the grape to snap when they bite into it. This firmness also makes the eating grape better equipped for transporting across the country.

None of this helps the winemaker. Firmer means more effort is need to crush and/or press the grape. Firmer also means that there will be less juice per pound of grape with an eating grape than with a wine grape. All these things mean making wine with eating grapes is more work.

Also, the breeding has also been done at the expense of the grapes inherent flavor. While the sweetness, acidity and firmness of the eating grape are optimal for popping in your mouth, if you ferment the sweetness away, the flavor that is left behind is not all that flavorful. Not much consideration is given to this aspect of the eating grape when being bred eating.

Having said this, I don’t want to discourage you from giving it a try. Making wine with eating grapes grapes is fine if you want to have some fun learning about the wine making process. This process is exactly the same either way. It’s just that you should not expect too much as a final result. The wine will be very drinkable, but lack flavor and character.

You can find more info on this matter in the blog post: Table Grapes Vs. Wine Grapes. You can also find a Thompson grape wine recipe on our website. Thompson grapes are a classic eating grape, so this wine recipe should work fine for any eating grape you come across.

Happy Winemaking,

Ed Kraus

———————————————————————————————————–

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

Bitter, Special Bitter, ESB – Brewing English Pale Ales

Bitter is the term given to a category of English pale ales, named for their relative bitterness compared to the English mild ale. Though they’re called bitter, they’re no more so than your average American pale ale. Ideally, English bitter ales should be session-able. Imagine drinking them in rounds at the local pub.

Bitter is the term given to a category of English pale ales, named for their relative bitterness compared to the English mild ale. Though they’re called bitter, they’re no more so than your average American pale ale. Ideally, English bitter ales should be session-able. Imagine drinking them in rounds at the local pub.

The bitter ales tend to be categorized by their original gravity. “Ordinary bitter” or simply “bitter” refers to the lowest gravity ales. These are ideal for a long day of drinking at the local watering hole. Stronger versions may be called “special” or “best bitter”. Finally, many American drinkers will recognize the name ESB, or Extra Special Bitter. The classic example is Fuller’s ESB (OG: 1.054), and many American brewers have adopted the term for their own English-style pale ales.

Though the naming convention is somewhat loosely defined in the UK, the BJCP has put some guidelines in place to give homebrewers and homebrew judges a framework for comparison. As you can see, gravities and IBUs, tend to increase as we move up the scale:

- 8A. Standard/Ordinary Bitter: OG: 1.032 – 1.040, FG: 1.007 – 1.011, IBUs: 25-35, ABV: 3.2% – 3.8%, SRM: 4 – 14

- 8B. Special/Best/Premium Bitter: OG: 1.040 – 1.048, FG: 1.008 – 1.012, IBUs: 25 – 40, ABV: 3.8 – 4.6%, SRM: 5 – 16

- 8C. Extra Special/Strong Bitter (English Pale Ale): OG: 1.048 – 1.060, FG: 1.010 – 1.016, IBUs: 30 – 50, ABV: 4.6 – 6.2%, SRM: 6 – 18

Ingredients

- Water – Many English pale ales are brewed with relatively hard water, which help give the hops a little “pop”. If you know you have soft water, consider adding some calcium sulfate, also known as gypsum, to your mash water.

- Malt – English pale ale malt, such as Munton’s, should form the base of the grain bill (~90%). Munton’s also make a very good light malt extract. Adding some Victory or Vienna malt will bring in some toasted flavors and a pound of Caramel 40L malt will be plenty to give your beer a touch of caramel sweetness and golden to amber color. Some brewers will use sugar to increase gravity and to impart a dry finish.

- Hops – Kent Goldings is the classic hop for English pale ales. With aromas of citrus and spice it does very well in late additions. Fuggles is another popular English variety, and tends to be more earthy and woody. Bitter ales are sometimes dry-hopped.

- Yeast – The fruity esters derived from a classic English yeast strain are desirable. Safale-S04 is an excellent dry ale yeast.

- Priming – The English are famous for what is known as “Real Ale” — beer that is cask conditioned and naturally carbonated (as opposed to force carbonating under CO2 pressure). To the American palate, cask conditioned ales seem somewhat warm and flat — that’s the way it’s supposed to be! Homebrewers who bottle get a similar effect by using just 1/2 cup priming sugar in a five-gallon batch.

E.S.B. Partial Mash Recipe (from Homebrewing for Dummies):

“1-4-U, 2-4-ME S.B.”

6 lbs. Munton and Fison malt extract

1 lb. 40L crystal malt

.5 pound Victory malt

1 cup brown sugar

2 oz. Kent Goldings @ :60

1 oz. Kent Goldings @ :15

1 tsp. Irish Moss

Primary fermentation for 8 days at 65F

Secondary fermentation for 10 days at 65F

Yeast: Wyeast 1968 / London ESB Ale

**Tips: Prepare a yeast starter and dry hop with an extra ounce if Kent Goldings if desired.

Do you have a favorite bitter ale homebrew recipe? Share in the comments below!

———————————————————————————————————–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

Winemaking Terms You Should Know: Part 2

In an earlier post, we introduced a few home winemaking terms that you may or may not be familiar with. There are many terms to learn in home winemaking, and this post, like the previous post, will give you a brief introduction into just a few of those terms to help you get started in home winemaking, or perhaps brush up on some of the terms you may not have seen in a while.

In an earlier post, we introduced a few home winemaking terms that you may or may not be familiar with. There are many terms to learn in home winemaking, and this post, like the previous post, will give you a brief introduction into just a few of those terms to help you get started in home winemaking, or perhaps brush up on some of the terms you may not have seen in a while.

- Piquant: This term is French in origin, and can be used to describe different aspects of the home winemaking process. First, piquant is a term used to describe the tactile sensation noticed when the wine hits your mouth. Also, piquant can be used to describe a wine that has a slight chance of turning to vinegar. Finally, is can also be used to describe a wine that is about to undergo a secondary fermentation.

- Punch Down: In red winemaking, the skins and seeds of the grapes are left in contact with the juice for a period of time. What happens is that these solid pieces stick together and form a “cap”, which floats to the top of the juice. If left alone, this cap will completely cut off the fermenting wine from oxygen, resulting in significant reductive characteristics, and other negative consequences related to poor or failed fermentation. The act of pushing and stirring (i.e. punching down) this cap will allow the solids to contribute even more complex flavors and aromas into the wine, which would not happen had the cap not been punched down.

- Still Wine: This one is easy to remember if you think in terms of water. What’s the difference between still and sparkling water? Bubbles! What’s the difference between still and sparkling wine? Bubbles! A still wine is the finished wine that does not contain bubbles.

- Fixed Acids: Fixed acids describe any acid compound that is found naturally in the grapes or wine, acid that is added to the fermenting wine, or those acids that are created during the fermentation process. Specifically, fixed acids are stable compounds that are not intermediates to another compound. In other words, these are “stable” or “fixed” acids that aren’t in the middle of turning into something else.

- Hydrolysis: This term describes the chemical reaction of decomposition between some compound(s) and water. “Hydro” means “water”, and “lysis” means “to break down”: putting the two together, you have the breakdown by water. One example of hydrolysis in home winemaking is the catalytic conversion from starch to glucose. In wine, hydrolysis is a process that is catalyzed by certain enzymes that can either be added into the must, or enzymes that are created by the yeasts themselves.

———————————————————————————————————

Ed Kraus is a 3rd generation home brewer/winemaker and has been an owner of E. C. Kraus since 1999. He has been helping individuals make better wine and beer for over 25 years.

Be A Homebrew Champion — Enter a Home Brewing Competition

If you’ve caught the homebrewing bug, chances are that you’ve thought about submitting some of your beers in a home brewing competition. The cost is usually minimal — maybe $5-7 per entry — and the payoff can be huge. Many home brewing competitions offer as the grand prize an opportunity to brew your batch on a commercial system. Win a Pro-Am competition, and your beer could be served at the Great American Beer Festival! What could be cooler?!

If you’ve caught the homebrewing bug, chances are that you’ve thought about submitting some of your beers in a home brewing competition. The cost is usually minimal — maybe $5-7 per entry — and the payoff can be huge. Many home brewing competitions offer as the grand prize an opportunity to brew your batch on a commercial system. Win a Pro-Am competition, and your beer could be served at the Great American Beer Festival! What could be cooler?!

There are a couple basic formats for home brewing competitions to be aware of, the open festival and the closed competition. In the festival format, you’ll be placed behind a table to serve your homebrew to the attendees and the judges. It’s a fun opportunity to “sell” your homebrew and yourself to other craft beer fans. Awards may be for different style categories, “People’s Choice”, or superlative-style prizes like “Strangest Ingredient” or “Best Use of Hops”.

The closed home brewing competitions are usually, but not always, BJCP-sanctioned events where beers are submitted within certain style categories and are judged side-by-side with other styles in the category. These competitions a great because you’ll get score sheets with helpful tasting notes from each of the judges. Keep an eye out for opportunities to judge or steward at the event! It’s a great way to develop your sensory and tasting abilities!

Advice for Homebrew Competitions

To help you maximize your home brewing competition success, here are some tips:

- Brewing a standard style? There will likely be a ton of pale ales, IPAs, and brown ales. Make sure you’ve tried the beer recipe at least once before, because competition will be stiff for the most popular beer styles.

- If you can, submit more than one beer. This will greatly enhance your odds at gaining recognition for your brews.

- Not sure which style category your beer fits into the best? It’s usually ok to submit the same beer into more than one category. Read the competition rules for details.

- Look for home brewing competitions outside your immediate area. Most competitions will accept mail-in submissions. Just don’t mail USPS — it’s illegal to ship alcohol via the postal service!

- Brew outside the box to stand out from the crowd. This works well for a festival style home brewing competition, where people really let creativity fly. If you have something crazy to bring people to your table, this will increase the chances that they will try your other beers too. Before you know it, everyone will be telling their friends, “Hey, did you try that crazy beer over at table 17?”

What advice do you have for homebrew competition success?

——————————————————————————————————

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.