Unless adhering to the strict rules of Reinheitsgebot, brewers will sometimes use ingredients that fall outside of the main categories of malt, hops, water, and yeast. The use of these beer brewing additives can greatly improve a beer’s clarity, fermentation performance, or flavor.

Unless adhering to the strict rules of Reinheitsgebot, brewers will sometimes use ingredients that fall outside of the main categories of malt, hops, water, and yeast. The use of these beer brewing additives can greatly improve a beer’s clarity, fermentation performance, or flavor.

This is a guide to some of the most common beer brewing additives used in home beer making.

Beer Finings/Clarifiers

These additives, often called “fining agents,” help to improve the clarity of your homebrew:

- Irish Moss – A coagulant added at the end of the boil, Irish Moss helps proteins form into clumps and settle out of suspension. For a five-gallon batch, add 1/2 tablespoon during the last 15 minutes of the boil. Made from seaweed, Irish Moss is sometimes referred to as “carrageenan.” Of these beer brewing additives, it’s the most commonly used.

- Gelatin – Gelatin is a colorless and tasteless compound that attaches to negatively-charged particles in your beer, helping them settle out of suspension. For a five-gallon batch, dissolve 1 teaspoon of gelatin in 1 cup of hot, pre-boiled water. Once dissolved, let cool and pour into the secondary fermenter, racking your beer on top of it. Gelatin is derived from animal collagen, so don’t feed to your vegetarian friends!

- Isinglass – Made from fish bladders, isinglass is a very common fining agent used in both winemaking and brewing. But don’t worry — used properly, it won’t affect the flavor of your beer. It’s added to the secondary fermenter in the same way as gelatin. One teaspoon is sufficient for a five-gallon batch of homebrew.

Water Treatment

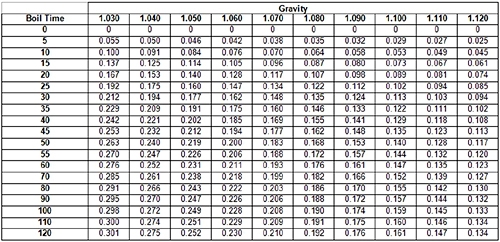

The minerals in your brewing water can have a profound effect on the flavor of your finished beer. Mineral beer brewing additives are typically used either to recreate a water profile from a certain part of the world or to adjust the mash pH. It’s generally recommended to get a water profile report of your city water, before adding minerals. Otherwise, start with reverse osmosis (RO) water, which has had all minerals removed, then add the ones you need.

- Burton Water Salts – These minerals are added to brewing water to simulate the water profile of Burton-on-Trent in the UK. They are often used when brewing English pale ales (think Bass Pale Ale). This mix includes papain, an organic compound which helps to prevent chill haze.

- Calcium Carbonate – Also know as chalk, calcium carbonate is a food-grade mineral blend. It’s one of the few beer brewing additives that raises mash pH (lowers acidity). Carbonate-rich water can help enhance hops bitterness.

- Gypsum – Gypsum is a mineral blend composed of calcium sulfate. It lowers mash pH.

- Magnesium Sulfate – Magnesium sulfate helps to lower mash pH.

- Yeast Nutrient – In addition to sugar, beer yeast requires certain nutrients in order to reproduce and convert sugar into alcohol. When it comes to brewing beers made with a high level of adjuncts, yeast nutrient can give the yeast an extra boost that will help them complete fermentation. It can also help achieve a lower final gravity and a drier tasting beer with less residual sugar.

Preservatives

- Ascorbic Acid – Also known as vitamin C, ascorbic acid acts as an oxygen scavenger. Oxygen in beer creates oxidation, which results in stale flavors, often described as wet cardboard. Add a 1/2 teaspoon to your beer when it’s time to bottle.

Do you use beer brewing additives in your home beer making, or are a home brew purist?

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling.