Many craft beer aficionados have heard the story about where the name “India Pale Ale” (or IPA’s) comes from. In short, to supply the colony in India, British breweries made ales with increased amounts of hops, taking advantage of the plant’s antimicrobial properties to ensure that the beer would survive the long trip. The American version of the IPA is more robust than the English version and also uses American-grown ingredients. But before I get into to brewing an American IPA, I’d like to share a little more about some of the history behind the style.

Many craft beer aficionados have heard the story about where the name “India Pale Ale” (or IPA’s) comes from. In short, to supply the colony in India, British breweries made ales with increased amounts of hops, taking advantage of the plant’s antimicrobial properties to ensure that the beer would survive the long trip. The American version of the IPA is more robust than the English version and also uses American-grown ingredients. But before I get into to brewing an American IPA, I’d like to share a little more about some of the history behind the style.

I recently picked up Ray Daniels’ book, Designing Great Beers, and learned a couple interesting tidbits about pale ales and IPAs. First, that pale ales were a product of the Industrial Revolution. The advent of steel allowed British maltsters to build better kilns, which gave them increased control over their product, which in turn made pale malts possible. Secondly, that these pale ales were considered beers for high society, while the lower classes stuck with the dark beers, like stouts and porters.

I found this quote, from 1934, to give an interesting perspective on the popularity of the style:

“[The India Pale Ale] is carefully fermented so as to be devoid of all sweetness, or in other words to be dry; and it contains double the usual quantity of hops; it therefore, forms a most valuable restorative beverage for invalids and convalescents.”

I don’t know about you, but I always feel better after an IPA! Now, back to brewing!

The BJCP Style Guidelines give us some parameters for brewing the American IPA (style 14B). The overall impression of the beer should be “an American version of the historical English style, brewed using American ingredients and attitude.” Whatever you do, don’t forget the attitude!

Here are the more easily measurable characteristics for an American IPA:

- IBUs: 40-70

- Color (SRM): 6-15

- OG: 1.056-1.075

- FG: 1.010-1.018

- ABV: 5.5-7.5%

Now, let’s look at some of the specific ingredients you might use for brewing your own American IPA:

Grain Bill

- All-Grain: Start with a well-modified US 2-Row Malt for the base of your grain bill (70% or so). Then use 1-2 pounds of Crystal Malt (20-40L) for color and caramel malt flavor. If you want, try a little (up to 5%) of Munich, Vienna, or Biscuit Malt for added complexity.

- Extract: If brewing with extract, use light or pale malt extracts and consider steeping some crystal malt for flavor and color. Consider the Muntons Connoisseur Kit Type India Pale Ale kit, which contains malt extract that has already been hopped.

Hops

- An American IPA should be brewed with US-grown hop varieties. Consider using Cascade, Centennial, Columbus, Chinook, and/or Willamette. Use 1-2 ounces during the boil for each of your bittering, flavor, and aroma additions. For increased hop aroma, dry-hop your beer by adding an ounce or two of hop pellets to the secondary fermenter.

Yeast

- Use a classic American ale yeast, such as Safale US-05 or Wyeast’s #1056 American Ale. American IPAs should have a “neutral” fermentation character, so be sure to keep the fermentation temperatures within the acceptable range for your chosen yeast strain.

Follow the above guidelines and profiles for brewing an American IPA, and you’ll have a beer that is tasty and to style. What’s your favorite IPA? Do you have an American IPA recipe you’d like to share in the comments below?

Til next time…Cheers!

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

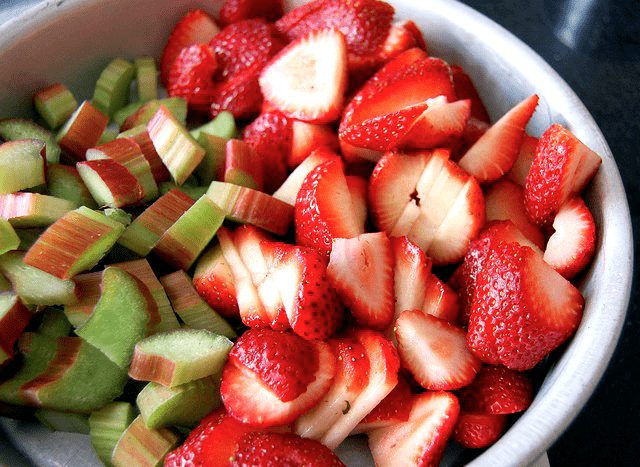

Every so often we run across someone who is making wine with bread yeast. Yes, I’m talking about the plain ole’ yeast you pick up in the baking section of your local grocery store. And every time I hear of someone using bread yeast, the question that always screams in my head is, “why?”

Every so often we run across someone who is making wine with bread yeast. Yes, I’m talking about the plain ole’ yeast you pick up in the baking section of your local grocery store. And every time I hear of someone using bread yeast, the question that always screams in my head is, “why?”