I recently brewed a Munich Dunkel lager. Everything about the brew day went smoothly, but a mysterious flavor presented itself later on. What happened?

I recently brewed a Munich Dunkel lager. Everything about the brew day went smoothly, but a mysterious flavor presented itself later on. What happened?

My theory: I had an excessive Maillard reaction in my beer while brewing, resulting in an attack of melanoidins. I know these may be some strange words for some of you, but please hear me out.

First let me share how my brew day went.

I was determined to brew a full five gallons of an all-grain batch, despite the fact that my brew kettle only holds five gallons. (A five-gallon batch of all-grain homebrew ought to have a kettle 7.5-gallons or larger.) The plan: mash enough grain for the five-gallon batch, collect 6+ gallons worth of wort by taking the first runnings, condensing, then the second runnings, condensing, and so on until I had enough sugars in the wort to eventually cut the batch with water and still reach my intended gravity. The brew day was long, but everything went pretty smoothly. I cut the batch with pre-boiled, pre-chilled water just before kegging to make my beer 5.6% ABV.

When I tasted the beer after secondary fermentation, I was excited by the depth and intensity of flavor. After packaging the beer, however, I was a little surprised to find a lingering sweet toffee flavor. Was it something in the beer recipe? The ingredients? That didn’t seem likely since some Munich Dunkles are made with as much as 100% Munich malt. Was the beer under attenuated? No. 71% attenuation is on par for Bavarian lager yeast. Was the beer under hopped? That couldn’t be it either. Even after diluting, my calculated bitterness was 25 IBUs. There must be something else at play.

Some online research led me to a new hypothesis: melanoidins.

What are melanoidins?

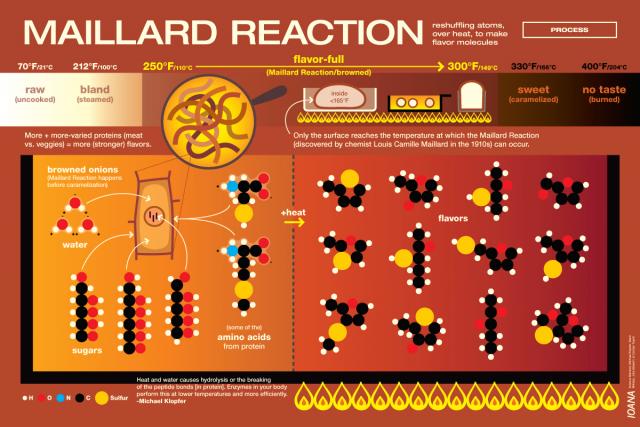

Melanoidins are formed when sugars and amino acids react together while heated in the presence of moisture. This reaction is called the Maillard reaction. The Maillard reaction is responsible for browning and flavor development in a variety of cooking applications. It’s often confused with caramelization, but in the context of boiling wort, what we usually encounter is the Maillard reaction in beer or home brewing.

Melanoidins are formed when sugars and amino acids react together while heated in the presence of moisture. This reaction is called the Maillard reaction. The Maillard reaction is responsible for browning and flavor development in a variety of cooking applications. It’s often confused with caramelization, but in the context of boiling wort, what we usually encounter is the Maillard reaction in beer or home brewing.

Melanoidins, which contribute flavors of toffee, nuts, and bread crusts, are present in some degree in a variety of malts, but can also be developed during the boil. The chemistry gets complicated pretty quickly:

“…reducing sugars interact with amino compounds (e.g., amino acids, simple peptides) to initially yield Schiff bases. These give rise to aldosamines and ketosamines by Amadori rearrangements. The latter may condense with another sugar molecule to form diketosamines, which are unstable and break down to give a range of products including hydroxymethylfurfural and reductones, and some of these products interact and polymerize to melanoidins.” – from “Melanoidins”, by Hornsey, Ian. The Oxford Companion to Beer. Oliver, Garrett; Colicchio, Tom (2011-09-09).

Makes complete sense now, right? Ha!

Let’s try the graphic approach.

My theory is that the prolonged boil in this particular brew day resulted in an excess of melanoidin formation. The Munich Dunkel is supposed to have some melanoidin flavor, so it’s not a tragic fault, just a little out of balance. Luckily, I found that by increasing the carbonation on the keg, I could reduce the impact of the toffee-like after taste caused by the Maillard reaction in my beer.

Two lessons here:

- Pay attention to your boil time. Don’t go lengthening your boil time willy-nilly. While an extended boil may be beneficial for a Scotch ale, bock, or stout, it wouldn’t be appropriate for a lighter beer like a Kölsch or a pilsner.

Brew within your limits. If I had been content with a three-gallon batch, I probably could have avoided the excessive melanoidins. Alternatively, I could have brewed two smaller batches, or done a partial mash brew using Munich malt extract instead of working so hard to condense the wort.

Brew within your limits. If I had been content with a three-gallon batch, I probably could have avoided the excessive melanoidins. Alternatively, I could have brewed two smaller batches, or done a partial mash brew using Munich malt extract instead of working so hard to condense the wort.

Well, lesson learned. But that’s one of the fun things about brewing, right?

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder and editor of the Local Beer Blog.

There is an error in your discussion. The melanoidins are polymers that form from the products of the Amadori rearrangement, and aldol condensation. They give color, but no flavor. However, the compounds your are talking about also come from the Maillard reactions. In particular, the furfurals provide that characteristic caramel flavor.

Dave: thanks for the interesting article.

I just started homebrewing myself, mainly to better understand the applications of the juice concentrates and purees that I sell.

I have found similar results when over cooking with juice concentrates.

If the brewer wants to expand the flavors (and surprise her/himself) while still using natural ingredients like these, the most common way is by adding (0.5-2%) juice concentrates to the batch prior to final colling and storing. You may want to (or not) filter. There are some clarified concentrates that will still allow for a clear light/pilsner.

Some concentrates may have high Brix levels, so there should be some analysis prior to their addition.

Cheers! Olman Castro