After boiling your homebrew beer for an hour, you may think that you’re done. Not quite. There are still a couple more steps that can go a long way towards improving the quality of your homebrew. One of these is chilling the wort after the boil, and there are several benefits for doing it quickly. Here’s some information on why you should chill your wort quickly and how to chill your wort quickly.

After boiling your homebrew beer for an hour, you may think that you’re done. Not quite. There are still a couple more steps that can go a long way towards improving the quality of your homebrew. One of these is chilling the wort after the boil, and there are several benefits for doing it quickly. Here’s some information on why you should chill your wort quickly and how to chill your wort quickly.

There are three main reasons why we chill the wort in the first place:

- To reach yeast pitching temperature – The ideal pitching temperature for your beer yeast will vary depending on the style of beer you’re brewing and the yeast strain itself, but in most cases it’s in the ballpark of 70°F. Pitching too warm could cause some strange off-flavors or even worse, kill the beer yeast. Just follow the instructions on the yeast package and you’ll be fine.

- To coagulate protein – This is an important reason as to why you should chill your wort – to produce a quick, sharp “cold break”. Chilling the wort quickly will help the protein in the wort clump together and settle out. This reduces the amount of protein in the final product and helps to achieve a clearer, better looking brew. The faster the change in the temperature, the better the cold break. The cold break can be aided by adding 1 teaspoon of Irish Moss during the last 10-15 minutes of the boil.

- To reduce the risk of contamination – Warm, sugary wort is the perfect place for wild bacteria and yeast to grow. The more quickly we can get the wort from the kettle to the fermenter, the better. But don’t let this make you panic! If you chill the wort quickly and do your best to reduce exposure to the air, your beer will turn out fine.

So, now that we’ve learned reasons why to chill a wort and why it helps to do it quickly, what’s the best way to accomplish this? How do we chill a wort quickly? Homebrewers have a couple of options:

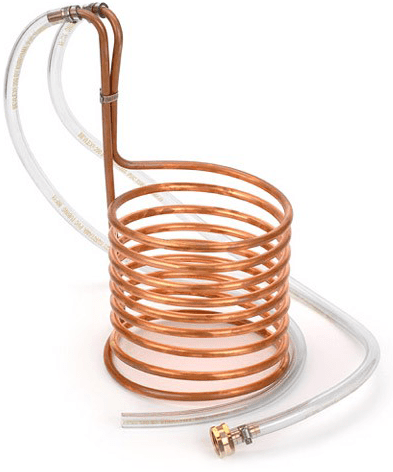

- The wort chiller – The fastest and most effective way to chill wort quickly is with a wort chiller. An wort chiller is basically a coil of copper with a couple of hoses attached. One hose is the cold water inlet and attaches to a faucet. The other is the hot water outlet. By putting the wort chiller directly into the wort and running cold water through it, the water will pick up the heat from the wort on its way through the coil and out the other hose. This method can bring the wort to pitching temperature in as little as 20

minutes, saving a lot of time and achieving a really good protein break. You’re likely to use a few gallons of water as you do this, so see if you can recover the hot water coming out of the wort chiller and use it for cleaning later on. There are also plate wort chillers. With these, the beer is being ran through a cold plate that is being cooled with running water.

minutes, saving a lot of time and achieving a really good protein break. You’re likely to use a few gallons of water as you do this, so see if you can recover the hot water coming out of the wort chiller and use it for cleaning later on. There are also plate wort chillers. With these, the beer is being ran through a cold plate that is being cooled with running water.

- The ice batch – Chilling a wort with an ice bath works best for homebrewers boiling three gallons or less (otherwise it takes too long). Simply submerge the kettle in a sink filled with ice, then fill the sink with cold water. A deep sink works best – see if you can get the top of the ice bath to be even with the top of the wort. You may need to change the water a few times to get down to pitching temperature. You can also cock the drain plug so that water is slowly draining, while water is running at the same rate from the faucet.

Now, you know how and why to chill a wort quickly. So the next time you brew, focus on making sure you chill your wort quickly. You’re likely to notice a difference in both appearance and taste.

What method do you use to chill your wort?

—–

David Ackley is a beer writer, brewer, and self-described “craft beer crusader.” He holds a General Certificate in Brewing from the Institute of Brewing and Distilling and is founder of the Local Beer Blog.

Sometimes a beer recipe can be better than the sum of its parts. This week’s amber rye ale beer recipe is a mash-up of two excellent beer styles that are great for fall brewing: amber ale and rye ale. The amber ale brings a malty flavor, medium to medium-full body, and a rich amber color, while the rye brings a distinctive spicy grain note. The hop flavor on this beer is noticeable with a spicy hop character, but the bitterness is balanced at just over 30 IBUs. It’s an American-style ale of moderate gravity that should make a balanced beer to enjoy throughout the fall season.

Sometimes a beer recipe can be better than the sum of its parts. This week’s amber rye ale beer recipe is a mash-up of two excellent beer styles that are great for fall brewing: amber ale and rye ale. The amber ale brings a malty flavor, medium to medium-full body, and a rich amber color, while the rye brings a distinctive spicy grain note. The hop flavor on this beer is noticeable with a spicy hop character, but the bitterness is balanced at just over 30 IBUs. It’s an American-style ale of moderate gravity that should make a balanced beer to enjoy throughout the fall season.

All-grain brewing is the closest thing to being a professional brewer. If you’re already brewing with

All-grain brewing is the closest thing to being a professional brewer. If you’re already brewing with